What If RSS Had Won? Rethinking the Web's Original Architecture

- 12 minutes read - 2441 wordsMy colleague Max dropped a casual observation the other day that struck me (paraphrased):

There’s not a single day where I don’t wonder: “What did we lose in failing to make RSS the most foundational tool in everyone’s Internet consumption?”

There’s a couple of interesting implicit ideas here:

- An internet experience where user agency and control is prioritized versus holding them in thrall like gawping punters is possible

- An internet experience that is not a panopticon of surveillance capitalism designed to harvest us as fodder to an advertising Moloch machine is possible

- An internet experience that allows creators to practice their craft as a career is possible. Which:

- Affirms the social and economic value of expertise, training, and insight versus booing the experts on cable news

- Undermines the ad-syndicate rentiers flourishing

I can imagine this agency-embracing alternative vision of the internet because I was there at all the forks along the way. I saw how we gently nudged ourselves ever-closer to a Burroughs-like Interzone. It wasn’t always like this, and I will tell you how we were slowly cooked alive – and how the escape is still there. To Max’s point, RSS was an agency-extending technology and it remains a powerful brick ready to be launched, Stonewall-like, into the torment nexus of the “attention economy.”

Let me be your tour guide on the footpath to hell, and, please, grab a brick on your way out.

How We Got Into This Mess: Technical Stunting of Agency

The early internet had email providing a federated, opted-for experience. Your address would promulgate person-to-person or via other broadcast media (newsgroups, published articles) and new mail would find its way to your inbox.

The early internet also had Usenet, a collection of forums or “newsgroups.” You would opt in for a given newsgroup by “subscribing” to it and then get new updates to it. Reddit is basically a re-hash, via the web, of Usenet.

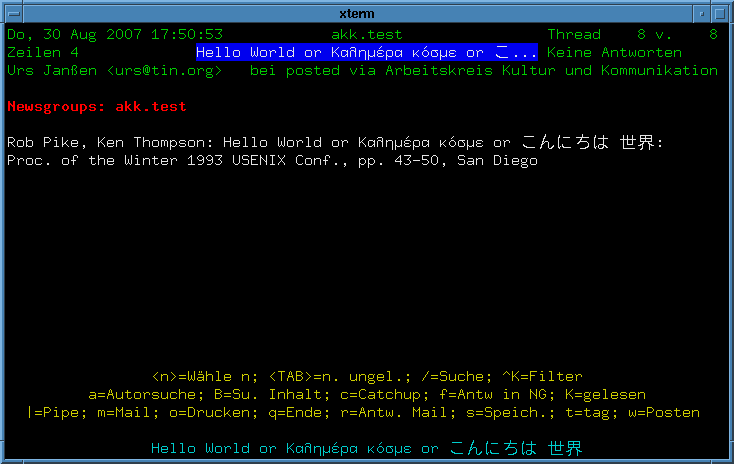

News as I first saw it: opt-in, targeted, no images, no ads

In both cases, you had full agency and the right to catch up on only the incremental deltas that interested you. So why wasn’t the Web also crawled and delivered on our digital doorstep? Simple: when the punters (you and me) control the flow of information, we control the terms of commerce; there’s no room for a middleman or rentier.

If our digital-rentier overlords could create an internet that got us on the turf of the advertiser or vendor with geegaws, loss-leaders, and pitches, then the rentiers could create and siphon a cut from every transaction made at the world’s largest mall.

Thus the builders of those malls, the venture capitalists behind Netscape, AOL, et al., made sure not to miss mining this lode. Given finite resources, they could focus on value extraction or focus on giving the punters a voice in the commercial conversation. They, opted for the former.

Lest I demonize these actors unfairly, the technical challenges were significant. Two crucial features were skipped in the rush to commercialize:

- Local synchronization and caching

- Micropayments to creators

Both were technically non-trivial in 1995. Synchronization would have:

- Required data standards that didn’t exist yet

- Consumed precious hard drive space voraciously

- Become enjoyable only with caching technology that hadn’t been invented yet

And micropayments would have:

- Required negotiating with banks about an unproven technology (“Web? Who is web?”)

- Necessitated the considerable social shift that let people plonk down their credit card data on a web site

Both these components represented a coordination problem of staggering complexity. While it was technically possible, it might have been socially possible. Nevertheless we were left with a web that privileged commerce and profit (“mall”) over reflection, curation, and civility.

And the commercial applications to warrant tackling a coordination problem of this scale were hard to imagine in practice. Suppose you did have micropayments. If you bought Metallica’s “Black Album” on digital media, you couldn’t readily take it with you. The iPod, smartphones, fast cable transfer technology—none existed. What would the update synchronization looked like in the era of long distance (‘memba ‘dat?) on dial-up? How many “I didn’t realize the computer was configured to dial long distance” support calls would browser companies have to field?

So instead of solving these hard problems, the browser companies made a choice for us: they shifted the responsibility of refreshing information flows onto users and gave us bookmarks as consolation.

And so, it wasn’t “Find what you need as delivered by digital genies” it was “Let’s Go to The Mall.” And go back; and go back; and go back. Engaging in capitalism is fun per se!

“Robin Sparkles,” a parody of mall pop-singers (Tiffany, Debbie Gibson) of the late 80’s as seen on “How I Met Your Mother.” Her reference to then-PM of Canada Brian Mulroney and his Regan-adjacent mall-prosperity gospel is choice.

But a mall is a funny thing. If people don’t come, it’s a big expensive box, surrounded by concrete. So the rentiers had to find something to pitch us to keep us walking the rungs of our bookmark managers. They found the best product pitch ever: good, free shit.

The Era of Amazing Quality for Nothing

The rentiers needed us to come back obsessively, like circling suburban dads angling for a bonus sample at Hickory Farms sausage station. The humble bookmark became their key technology: it taught users to poll endlessly—visit, visit, visit the digital storefronts scattered across the informational landscape.

But storefronts need fresh inventory to lure return customers. Content that had been valuable enough to subscribe to was suddenly mortgaged for eyeball traffic. Through the late 90’s, amazing collaborations baited the punters: free newspaper articles, free classifieds, free singles ads, free music (pace Lars Ulrich).

At places like Gannett, Knight-Ridder, Dow Jones, the Times, the same rook-cum-tragedy played out:

Faced between the rock of slowly bleeding revenue while giving content away and the hard place of slamming doors on customers, they opted for the former in desperate hopes that a new revenue model would appear.

By era’s end, the public believed two fatal things:

- They had a right to free, awesome content

- They had to poll to get it

And content producers learned:

The only way to extract any former subscription revenue was to bedizen every square pixel with ads.

The Trap Snaps Shut

But there’s the crucial trick, the binary split in timelines: they convinced us that polling was the only option. We forgot about curated federating that we used in mail programs like Eudora or like we saw in the Usenet example earlier.

Once the rentiers knew we’d return, they could broker our visits through referral fees and ad auctions. With perfect information about punters, the poor saps (i.e. us) could be loaded, packed, and sold. The essential axiom emerged:

The more perfect the information about the punter, the higher the fee for putting likely customers in front of storefronts

While this started unimaginatively by putting a virtual storefront in front of the destinations with slick ads, streaming audio, and streaming movies in the form of portal sites (My Yahoo! et al.), that was thinking too small, thinking on a child’s level, thinking about a commercial model that would have been obvious in any trading empire like Rome, Athens, or Babylon.

If you were willing to burn cash at a truly spectacular level, you might be able to build a system of perfect punter information: social networking as an ad network was becoming visible to those who dared break every rule in the MBA book.

Les Arbres du Mal: Social Media Perfects the System

Google, Facebook, Alphabet, Meta: they’re all variations on selling you to information brokers who sell you to advertisers.

Social media was the information harvester’s dream. People volunteered their births, deaths, marriages, divorces, friend groups, geotagged photos—dozens of market signals providing an ever-richer punter profile. They talked “community” and “connection” and transcending the legacy rules of the nation state. But these careless people really cared about tranches of eyeballs.

- Can we give you photos (scan the metadata)

- Can we give you storage (scan the metadata)

- Can we give you email (scan the metadata)

- Can we give you chat (scan the metadata)

- Can we give you a mobile phone operating system (scan the metadata)

- Run it fast forward, with optical character recognition and large language models, we can look at the data and not just the metadata. They just had to store it for 20 years.

We’re just a big family…that loves to exploit you. And will hack your phone and leave you vulnerable or will undermine democracies to keep you together. Wait. Why are you making us hurt you?

And then they got naughty with it:

- Cambridge Analytica

- Third-party cookies harvested data across the web

- Backdooring your phone to provide better tracking data when you thought you weren’t sharing anything

And here capitalism cruelly buried its most-precious victim: truth. Why risk a punter by dispelling beliefs about January 6th or vaccines? Better to keep them engaged, targeted, quantified, and resold. Truth was tilled under like loam for a failed crop.

Fast-forward to now: we’re all sold, relentlessly, while being goaded by hatred, love, and ennui to STAY TUNED! And here we are, the sick Last Men of the technical age.

…But this torment nexus falls apart with one thing: dropping the polling model and returning agency.

The 2005 Inflection Point: When We Could Have Changed Course

But here’s the tragedy: by 2005, we had another chance to choose agency.

Computer costs had plummeted. Broadband was ubiquitous. Web standards were

mature and robust. Online banking was established at every major institution.

JavaScript was undergoing a renaissance that suggested end-user remixing of

websites in sophisticated ways was now possible. Instead of abusing the

<iframe> tag, as I once did to create personalized landing pages, programmers

could harvest data endpoints and integrate them into personalized experiences.

Yahoo!’s bold engineering/innovation around “Pipes” was a widely-admired,

respected, and emulated prototype.

These data flows could be democritized with RSS: a simple serialization format that allowed any website – personal or commercial – and consumers to synchronize. With RSS, we could have stitched together a thousand voices, paid them for their research, and created the most meritocratic press ever. Google Reader and NetNewsWire proved it worked beautifully.

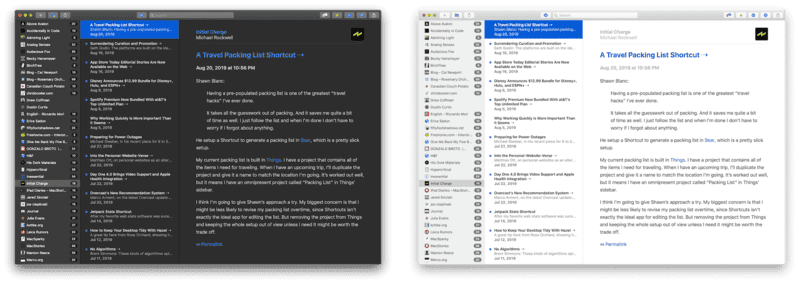

NetNewsWire, a more civilized way to consume the, ahem, “blogosphere”

We could have built a different web: one where you woke up to a federated amalgamation of content you chose, paid for through tiny automatic micropayments, free from algorithmic manipulation and dark patterns.

All the technical barriers that made the 1995 choice understandable were gone. Instead, we stayed in the Interzone.

A Taste of Federation: Visiting the “Fediverse” with Mastodon

If you want to preview what the Web could have been like, try joining

Mastodon. There, you’ll be the guest on an administrator’s machine, like a

BBS. When you first join, there’s nothing to see: just like when you’d open

your email inbox for the first time. Slowly you follow one or two people. Maybe

you respond to a post. They reply back in civil, informed tones. You find

communities of interest around individuals or topics (“hashtags” like

#skateboarding or #freebsd). Eventually, carefully, thoughtfully, and

slowly you grow your feed. Follow more and interact more, you’ll get more mail;

slow down or take a break, and the new updates will settle down.

Don’t you feel better already?

Pretty as Brooklyn on an early-Summer day

In addition, since you control the federation, you can filter topics or individuals. And since the distribution is federated, no company, or policy, or short path to quarterly targets can change these mechanics. I’ve been using Mastodon for 3 years and it’s still great.

Even better, if you decide you need a more efficient way of processing the input stream you’ve groomed, you can point to both people and topics via an RSS reader. There’s no need to be driven by FOMO that you might have missed one of your favorite poster’s content updates, process your backlog when you want, if you want – just like email.

And if you decide that it’s all too much: mark all read and start again. Your sanity and health should never have become the Web’s playthings. Mastodon provides a taste of what decentralized, federated social networking can be. Imagine what it would be like if this interaction model ran the Web. The rentiers would hate it. Maybe that’s grounds enough to give it a try?

What We Lost, What We Gained

Max’s daily RSS musing represents a kind of digital resistance—a return to the pull model that never quite caught on. RSS users don’t get algorithmic feeds; they get exactly what they subscribed to, in chronological order, without manipulation, with their filters and blocks respected. It’s the web as intended: a decentralized network where you choose your own information diet.

But RSS never became the default because it required too much intention, too much curation. It asked users to think about what they wanted to read rather than passively consuming whatever was served to them. In an alternate timeline, that intentionality would have been the web’s greatest feature, not its fatal flaw. And perhaps the real flaw is us; we who would prefer the Wonderbread of TikTok to the dense bread and split-pea soup of a curated digital experience.1

The tragedy isn’t just that we missed out on micropayments or RSS-centric architecture. It’s that we built a web that optimizes for capturing attention rather than serving human needs or objective truth. We created systems that profit from confusion, outrage, and endless scrolling instead of clarity, satisfaction, and genuine utility. We also allowed the rentiers to rob creators fucking blind. A reality where every internet user is armed with RSS as a transmission mechanism, an RSS reader, and perhaps even a personalized LLM agent to organize and assist seems vastly more humane than the unwashed internet. Seriously, go to YouTube on a new computer without a login, what’s default shown to people is…scary.

Maybe it’s not too late. Maybe the next generation of web technologies—fed by our growing understanding of what the current web costs us—can still learn from RSS’s quiet wisdom. Maybe we can still build a web that serves us, rather than a web that serves us (up).

The problem is choice

As the architect stated in “The Matrix: Reloaded,” the problem was and remains choice. RSS persists as do the rentiers who would sell our own spittle back to us as imported water. We made a choice, and it was the wrong one.