The Mind of AI and "Dead Ringers"

- 5 minutes read - 1059 wordsWe seem to be living through some sort of an AI blossom after the AI winter that began in the mid 1980’s. In the intervening years, many in the tech community had given up on the hope of AI. However, the rise of cheap, heavy-computation-friendly GPUs meant the birth of “machine learning,” “data science,” and “(un-)supervised learning” to train models. With these models trained, applications could be built that churned out uncanny and remarkably good results e.g. ChatGPT4.

For the first time in recent memory, it seems that specific-purpose, if not general-purpose, AI may be a fact of our lifetimes.

And this is just the beginning.

Not only are AI manipulating strings of text seemingly intelligently, they’re generating art and images from text as well. We’re even using AI to create new artifacts for special purpose. For example, an AI-designed aerospace product was recently commissioned by NASA. The component looks more like an alien spacecraft or biomechanical art than a functional component. But it functions to its purpose and meets the prescribed tolerances.

A human/AI collaboration to create new structural elements for space-borne telescopes

This product is eerily different, freed as it is from the burdens of humanity’s history of ideas around Earthbound biomechanical motion:

DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man

or Earthly geometry as in Euclid’s Elements:

Geometry as we know it is canonized here

or Earthly paradigms around materials’ behavior and economic constraints.

It’s trite, but necessary and profound to note:

Alien intelligences produce staggeringly alien artifacts.1

But can we see alien intelligence’s products among us today? I’m sure there are factual examples, but what came to my mind were the alien-looking artifacts the created by alienated among us in art. In the AI-designed space components, I saw an aesthetic similarity to the Gynecological Devices for Operating on Mutant Women from the 1988 David Cronenberg film, “Dead Ringers.”

The tools as envisioned by (fictional) Dr. Beverly Mantle: “Gynecological Devices for Operating on Mutant Women”

These devices are the product of the tormented minds (mind?) of twin gynecological geniuses, Drs. Elliot and Beverly Mantle (portrayed brilliantly in two performances by Jeremy Irons).

Luncheon with friends

But amid this reflection, I found myself asking why it’s so hard for human engineers to make the cognitives leaps to innovative and optimal designs that AI seem to do intuitively. If one asked 1,000 aerospace engineers to build a space component, I’d wager they’d all appear largely similar; I wouldn’t expect any/many to look like what NASA’s AI created. Why?

I think the answer lies in history and our relatively short lifetimes: we cannot conceive of the truly optimal because we have, of necessity, found it more practical and efficient to build off of or use what Earth’s natural selective pressures have already produced (pursuit of local maximum) rather than start anew and truly and exhaustively iterate to the optimal goal state (pursuit of true/global maximum). But that’s precisely what natural selection does ex nihilo…and it’s what AI do as well.

So our constraining factors, therefore, have to do with time and the finitude of our lives. What if we could run hundreds, if not millions, of experiments over lifetimes iterating to the desired end state? What if we could truly pursue the global maximum tabula rasa: each fiber, each atom could be tested, placed, swapped, tested, backtracked-against, etc. until it was a true symphony of optimal decisions. This freedom from what came before is why, I believe, alien intelligences’ artifacts look so, well, alien; that is, they’re not rooted in the imperfections that we take as necessary prior art as humans.

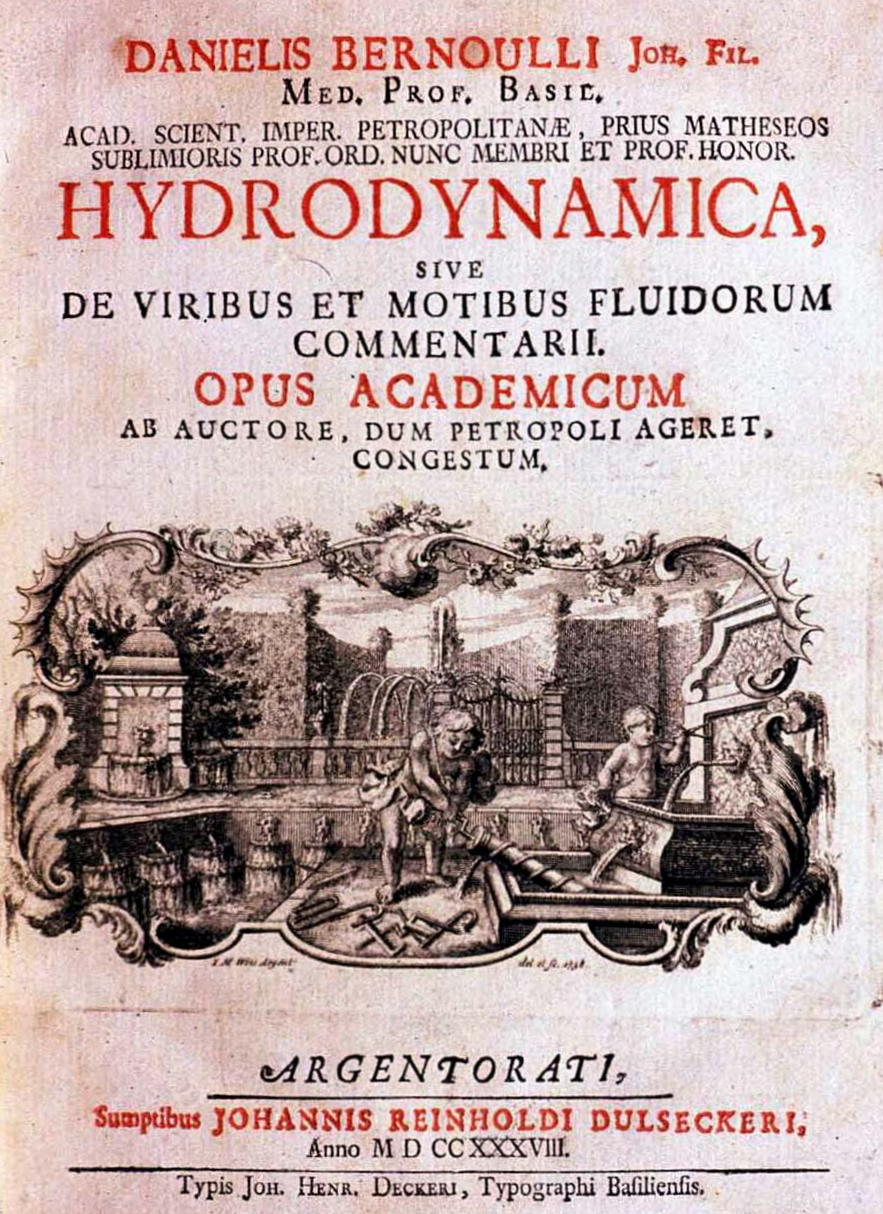

Put to the task of e.g. designing a wing, my mind immediately flashes diagrams of the Bernoulli effect

Cover page for Bernoulli’s Hydrodynamics

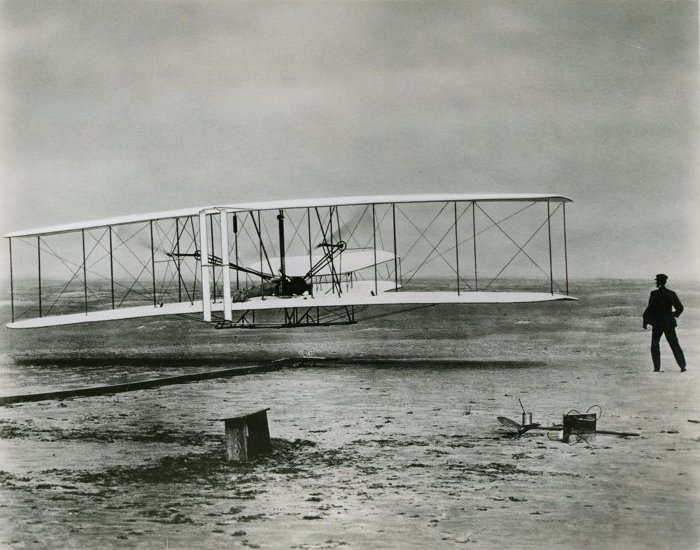

the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk

Powered flight at Kitty Hawk

and Concorde.

Supersonic flight

But an AI starts from true first principles (atoms, tensile strength, wind resistance, planar geometry) spending human lifetimes of study, inexhaustible, indefatigable, focused in pursuit of generating millions of designs, testing them, and iterating to perfection like accelerated natural selection. But from the perspective of the clock on the wall, it could spend these lifetimes of study in mere “wall-clock” minutes.

The AI could start with atoms, basic chemistry, basic materials science, unto considering how to link atoms into filaments, filaments into fibers. It could research the history of textiles and civil engineering. It could effectively “grow” the knowledge of how to “grow” solids. It would find that a thread could not generate lift, but that a matrix of filaments could create a sheet and a sheet could generate lift. The sheet would not be rigid enough to create enough lift, so it would be trashed, but layers of sheets could create solids and they could create the right amount of lift. Sure, it’s massively electrical-grid-inefficient, but the intermediary results could be cached and re-used later. Ultimately, like natural selection does, a minimal, niche-occupying, constraint-satisfying model could be found. The first design across the line. And it could look radically unlike anything that our human preconceptions would precondition us to expect.

Liberated from knowledge of bird and bat, Howard Hughes and Boeing, Goddard and von Braun, what might this alien Promethean genius, unbound, see that our current paradigms and assumptions blind us to?

And this is exactly what the AI behind the NASA part shown show did. It ran natural selection’s algorithm rapidly in order to evolve or grow an aerospace part, quickly, efficiently, running lifetimes of experimental optimizations in minutes to achieve a true maximum.

In some way, by creating a tool that can truly think from first principles, when we know it’s so hard for us, we’ve made ourselves spectators to the creativity of an untraceable, incomprehensible sort of insight from an unknowable other that, while correct, is cold, opaque, and alien. Can we love the intelligence that gives us these gifts of engineering? Must we fear it? Do we embrace it? Do we shun it? The answers here are in art, and Dead Ringers certainly has an opinion.

Footnotes

AI have surprised us before, e.g. playing novel and alien strategies in Go:

In Game Two, the Google machine made a move that no human ever would. And it was beautiful. As the world looked on, the move so perfectly demonstrated the enormously powerful and rather mysterious talents of modern artificial intelligence.