The Visual Genius of David Mallett

- 11 minutes read - 2192 wordsGen-Xers complaining about the loss of “their MTV” (the one that showed videos) is now itself, a joke. Gen X-enters-midlife inaugural series “Portlandia” went so far as to feature an episode where Portland-based Xers united with our Cronkite (Kurt Loder), and our Barbara Walters (Tabitha Soren), and our ready-made music-guru buddy (Matt Pinfield) to stage a coup against the channel’s current Gen-Z-oriented, “Teen Mom”-pushing programming director.

She doesn’t care about your nostalgia, Harms

It’s hard to sell someone else on their loss. No one, reasonably, wants to hear about how great the party (or New York City, or San Francisco) was just before they got there. So, perhaps against type to my generation, I’d like to not say what the later-born lost because they were born after MTV was paved over with boy-band-friendly, gonad-vaporizing “TRL” and insipid reality shows gone horribly wrong (What hath “The Real World” wrought?).

Instead, I’d like to recall what humanity gained in that early era of videos. In this post, I’d like to recall and celebrate a director who laid down a gauntlet to say “We could do this ‘video’ thing with artistry and daring, like this.” The director was Englishman David Mallet who, in his visionary collaborations with David Bowie made profoundly memorable, challenging, and daring videos. Bowie and Mallett’s videos hinted that the medium could be more than musical ads to sell records. It could be an art form unto itself.

Videos in Context

To appreciate what Mallett and Bowie did, we need to look at what their contemporaries’ videos looked like.

Expand for a retrospective of what early-80s videos looked like

The novelty and "What do we do now?" of the medium can be plainly seen in the ignorance and insouciance of the Beastie Boys' "Fight for Your Right" and Twisted Sister's "We're Not Gonna Take It."What they live on a set?

Or:

Even the millennia-old formula of male-gaze-heavy T&A tropes like Joan Jett’s “Do You Wanna Touch Me” and “I Love Rock n’ Roll” felt new.

This is so on-brand for Joan Jett: hollow-body guitar, bikini, boxing gloves. In the era of “Nine to Five,” she was prefiguring the 90’s feminism of Fiona Apple and Liz Phair.

If it’s any indication, doing a cheer routine seemed pretty reasonable in Toni Basil’s “Hey Mickey.”

Where did they get those costumes? BBC garage sale? And that synth riff is totally Elvis Costello. And what the hell is up with that guy with the sombrero..and…mallets hammering on Toni?

But sophistication and innovation were winding their way in.

The Cars’ “You Might Think” pushed the boundaries of bluescreen and computer graphics.

Miss you Ben Orr and Ric…

Videos were also gaining stories that enhanced or framed the narrative(s) of the music. Chrissy Hynde as a London waitress made a huge impression when I realized “Brass in Pocket” was about those strange-looking coins (pence) she pocketed in her waitress’ apron.

I also have to credit some musicians for seeing how a lot of studio movie could go to make fun entertainment: let’s just put Ozzy Osbourne’s “Bark at the Moon” as an example.

In many cases, these videos look like the band’s buddy from art school had rented out a studio and signed out the camera for a few hours (in many cases, they had). It was rough and garage and experimental and this medium had no predecessors. Because of this, the stakes were low and it produced glorious experimentation — and even some camp. Perhaps the most-campy video was also the most titanic video: Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” I think Stone Temple Pilots’ video for “Big Bang Baby” — possibly one of the last videos before their primary release channel was YouTube — was an homage to the videos of this era.

Definite shades of Toni Basil here

With examples like the Beastie Boys’ Fight For Your Right and even John Landis’ Thriller you can see what the status quo of videos looked like: unfocused, experimental, kids-borrowing-the-camcorder excuses to use the record company’s money for pizza and beer.

To show you what happened next, I give you Mallett and Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes:

Here’s my read of the video:

Interpretation of the "Ashes to Ashes" video

From the opening that looks like Tarkovsky's "Solaris," Mallett uses solarisation on the _film_ (yes, ***film***!) and other practical abuses of the medium to set the stakes that he and Bowie are here to challenge the viewer.Things are definitely not normal here.

We start with Bowie-the-clown, the apex of his performer status. In late-1970 to early-1980, Bowie was one of the most world-recognized superstars of music. He was at peak rock star and, at that apex, he sees himself as an elegant harlequin.

The use of a visual “stepping-in” video effect from the isolated beachside (using a green-screen portal), leads to an unmasked clown on that same beach. The video is telling us “the me that isn’t the character isn’t really me either.” That character, in-turn holds another visual portal to a “rubber room” in which the real Bowie is captive.

Real-Bowie reflects here honestly, but the Stage and the Clowns are his interlocutors. Before the second sentence is out, the light shifts (on a chord change) to hatchet lighting and spotlight which suggests that even when he’s locked away he’s wrestling with being a performer. He’s inviting us into the personal Hell of being Major Tom and being the creator of Major Tom.

We jump cut to a series of characters that I call the existentialist quartet: three forms of religious-looking figure and one ballerina are shown burning something. Burning the body of Tom? Or of Bowie? Or of the artifacts of the two? These iconic black-garbed figures recall the surrealist cover of Camus’ The Stranger (previously covered).

We fade cut to the clown, fully masked (Bowie at his most commercial). Far from resisting the quartet, he’s leading them. He’s leading these figurants with a bulldozer – the machine that is most appropriate for the burial of big things. For Bowie, nothing could be bigger than Major Tom and the impulse that lead Bowie-the-writer to create him. He’s suffering a nervous breakdown from carrying Tom’s baggage.

With our pathos roused, Bowie must bury Tom and must settle old scores. The score he’s going to share with us is the story of his drug addiction. The addiction was a means for handling that big space-faring elephant in the room. The next scenes and lyrics align to describe this struggle.

Mallett’s solarisation of ocean to make it black recalls some sort of hydrated inverse of Bowie’s turn in “Man Who Fell to Earth.” Instead of dying of thirst, he’s surrounded by the brackish undrinkable brine. I like to think it’s a metaphor for the ubiquity of narcotics available to him. Unsurprisingly, the fully-made-up clown is suffering withdrawal tremors as he smiles for one more photo.

We cut back to the interior of the rubber room. Bowie’s at rock-bottom here, he’s going to let us in on a secret. This scene corresponds to Bowie-the-junkie in recovery. I think this is hinted at by the presence of a blue square which recalls Bowie’s “Sound and Vision’s” – a song about kicking heroin use – lyric “Blue, Blue, Electric-Blue.” The next scene, while surreal, is also his confessional of loneliness.

Major Tom, Spaceman is situated in a suburban, post-war, household kitchen. Bowie said in interviews that he found Kubrick’s 2001 to be a metaphor for the social isolation he felt in postwar, suburban England. Mallett gives a literal view of that feeling: sterility, cleanliness, etc.

You see, the “Space Oddity” was the imagined escape for David Jones into a different life for himself, for a different future. Flash-back to the present, this future is coming at a cost, Jones is losing himself in his dream-turned-nightmare personas of “David Bowie” (in the rubber room) and “David Bowie, Superstar” (the harlequin).

The clown reckons with the truth: “I’ve never done good things / I’ve never done bad things.” He’s asking for Life or God to forgive him for the success of his dream as he literally drowns in the black waters.

We cut to Tom suspended in an alien landscape, is this Bowie accepting that he is an alien? Is the loneliness that Tom is an escape from something he can’t be freed from? Is he making peace with his nature? I don’t think we know and I don’t think Bowie or Mallett knew for sure either.

Back on the lonely beach, Bowie-the-clown sends doves (back to Bowie-the-junkie?): is it reconciliation or hope or forgiveness flying between the two worlds? I like to imagine it’s hope. The clown is saying it’s OK to bury him to be you again. Indeed, three years after this song Bowie would be in a radically different direction with the next two songs we’ll discuss.

At last, we cut to Bowie in conversation with a member of an older generation. For all of his freedoms, he’s accepting that maturity requires him to connect to the quotidian.

Other highlights are the makeup and Bowie’s supreme use of nonverbal communication.

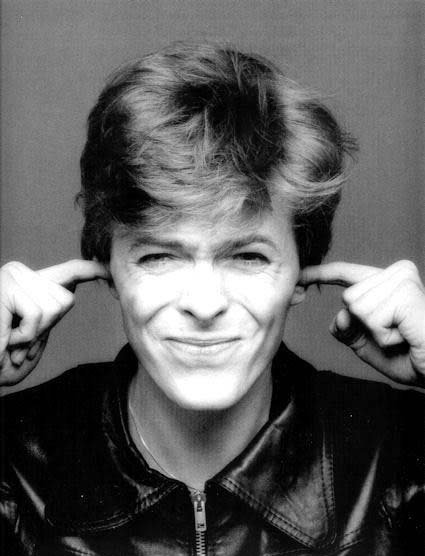

David Bowie “Hear No Evil” by Masayoshi Sukita

The makeup recalls Bowie’s extensive work studying mime and Noh theatre. It was perhaps this study of mime that gave him a profoundly effective means to communicate in videos. While he could only lip-sync, his body and facial expressions tell volumes on top of the story the song’s text alone.

In comparison to the previous contemporaries, this was something else. The richness for the eye also awakens a transcendent surrealist sense of communication. The images are so powerful they reach beyond words to some sort of collective unconscious of the Bowie-verse. In comparison, the first videos I listed in this post seem sophomoric in the extreme.

Three years later, Bowie and Mallett would reunite to make another video that communicates in symbols. This video also won Bowie “Best Video Performance (Male)” from the nascent MTV Video Music Awards, “China Girl.”

“China Girl”

“China Girl” is a Graham Greene-recalling vignette that wrestles with Imperialism, Empire, masculinity, and globalism. By turns it is erotic, symbolic, impressionist, mocking, and delusional.

Bowie here is recovered from his nervous breakdown and heroin use. He’s tanned, handsome and sporting the roll-brush and hairdryer look of the Wall Street-adjacent yuppieism. This handsome man, no longer the sickly depressive of the rubber room lures us in with a loungey crooner pantomime before using Mallet’s mastery of film manipulation to accentuate collective unconscious gestalt images (rice bowls, Gobi-esque desert, Mao-esque flags) to help us realize that the song is a dialog between Britishness, Imperialism and China and Orientalist fetishism. It’s staggeringly forward-looking as this is now the great question before all nations on the planet: What is China to us and what are we to it?

Bowie provides a beautiful reflection on Empire and its decline:

My little China Girl / You shouldn’t mess with me. / I’ll ruin everything you are. / I’ll give you television / I’ll give you eyes of blue / I’ll give you man o’ wars to rule the world [sung by a Brit!]

…that culminates in this iconic early days of MTV image…

Wow.

For me, this image is much more powerful than Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in the surf scene from “From Here to Eternity” that is later referenced. I’ll not do another deep-dive into the symbology of the video, but let it again be noted, this was a high-water mark amid its peers of the era.

“Let’s Dance”

The story here is far less symbolic, but again touches on many of the concepts of “China Girl” — empire, racism, exclusion, White privilege, capitalist heartlessness. Bowie takes a back seat while two Aboriginal actors show the burdens of being dark-skinned and poor in the rising country of Australia (in just a few short years the world would fall in love with Sydney during their Olympics).

Here “red shoes” are found in the Outback and symbolize an adoption of Anglo culture even as it mocks their rich history. Symbols of the aboriginal lovers dragging heavy machinery through the streets or being forced to scrub the filthy motorway assure us that they are aware and humiliated by the place forced upon them in this imperialist hegemony.

It’s worth noting that Australia’s history is as fraught as my own country’s and I’m in no place educated enough to comment upon it beyond this straight reading. I’ll only add that at the time this video was made, apartheid was still functioning in South Africa. Bowie, as he would do many times, speaks truth to power using his own privilege to ask whether what’s happening is right.

Conclusion

The Bowie / Mallett video collaborations were exceedingly special. They challenged us to think about videos differently. Thanks to them there would always be videos that pushed beyond obvious tropes like naked-ish women, live performance, and a good party. Madonna’s “Like a Prayer,” Guns n’ Roses “November Rain,” Metallica’s “One,” Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” would all go on to invite our eyes and brains to engage with the music at a richer level.