Quirky movies that don’t suck: "Lars and the Real Girl"

- 5 minutes read - 1062 wordsThis last weekend Lauren and I caught the anti-Darjeeling Mumbledy, a movie with quirk and actual heart, “Lars and the Real Girl”

Lars is a very young, very lonely, and painfully shy 27-year-old man who lives in the upper wint’ry wastes of The Mitten. He lives in a small, meagerly-heated garage adjacent to the big house where his brother and pregnant wife live. He drives his winter-reasonable Toyota hatch-back from his “Office Space” ( action figures and stuffed animals, yes, humorous destruction of productivity solutions, no ) job and on Sunday Lars shows up to church ( while the brother and wife attend Keillor’s “Church of Brunch” ).

What makes a “quirky characters” movie work is that the characters have time and space to breathe, to expand, to talk about their situation, at length, and to let you find ways to identify with them. If they are merely “zany and like action figures” ( or luggage, or frisbee golf ) for no apparent reason without an intimate bond to the viewer, then the magic fails and you wind up with a Darjeeling Mumbledy. But, if, in their subtle and vulnerable invitation, you see a reflection of your own quotidian loves, foibles, and failures, then, my friends, the magic is on.

So when we let Lars breathe we see that he’s in a painful phase that, I’d wager, just about everyone who reads my little review can identify with: he’s horribly lonely. In a conversation with Patricia Clarkson’s Doctor / Psychotherapist ( “you have to be, this far North” ) he asks her if she still feels lonely since the death of her husband.

Some days I feel so lonely I forget what day of the week it is.

What young man moved away from the farm doesn’t know this? What divorcee, widow, brother, or husband, what ex-girlfriend, ex-boyfriend, the girl left on the train station platform back home? In short, we all are Lars, getting by in spite of the oppressive blackness of loneliness in whatever way we can. To condemn that fragile tendril of love that pulls us together because it’s “immoral” or “he/she’s not like us” is to damn a soul to the slowest death of all: death by disassociation.

But how to flesh out the subtle undercurrents of loneliness, what this private madness does to the heart and the mind? Soliloquy and invective are not the best media for his message. How can the depth and subtle nuances of loneliness be revealed in a new way?

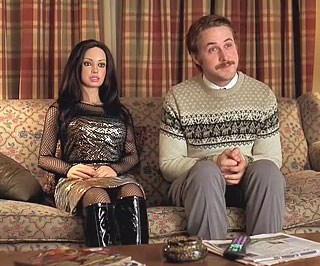

Enter “Bianca”. That is, Lars orders a “Real Girl”. A real girl is a fully, uh, functional, anatomically correct, uh, partnership doll. We’re talking 150 pounds of incredibly realistic-looking female with a synthetic skin and go-go boots.

While the townspeople immediately ruminate on Lars’ sexual designs on Bianca, we see that it was not horndoggery that brought the two together, it was Lars’ deep abiding need to love someone, even if that love could not be given back in equal measure. And in this we see a new face of loneliness, as Monsieur Hugo said, that while it is fine to be loved, a far, far finer thing it is to love.

Further, we see that aspect of projection that is so deeply hidden in deep loneliness. Lars projects the life he dreams he and his dream-girl living. He doesn’t force Bianca to wear risqueee clothing Bianca was shipped with, he immediately seeks to clothe her in the demure jumpers of his sister-in law. He sees cute winter wear and thinks “Wouldn’t that look great on her”. He fabricates in her life story that she is half-Danish to be like the, I assume, Danish-Americans both he and his brother represent (Lars and Gus[tav] - chances are in my favor ).

He imagines so much more than just sex – he imagines life: trips to the lake, a heartfelt serenade, taking his best girl to church, and introducing her to his brother and sister-in-law.

Director Craig Gillespie, thankfully, never leaves Bianca’s inanimate form as a Weekend At Bernie’s sight gag. When Bianca flumps over she is set aright and tenderly covered with a blanket. When she needs a bath, Gus and his wife oblige. Her beauty and texture are realized to be an asset as she “models” in the window of a mall boutique. In short, she’s real because the world relates to her, because they relate to Lars, and out of their love for this home-town boy turned a little odd, they realize he needs this relationship to learn to re-connect.

Lars’ path is shepherded by the fantastic Patricia Clarkson, who plays the aforementioned doctor. Together these two talk about loneliness and help Lars begin to break his emotional ice. Lars is so shy that mere touching feels to him as burning, and that social interactions drive him to painful wincing and panic-attack. Ryan Gosling does a great job conveying the desperation and the shame interwoven into his character. I’d never seen anything the gentleman had done before and I must say I believe he will continue to do great things in future.

And the wild-card in the whole story is the incredibly sweet, warm, and loving Margo played perfectly by Kelli Garner ( incidentally, mad propz for being fearless enough to go lite on the makeup, simple on the hair, and un-chic on the wardrobe: believable and fearless ). A girl whose winter-ready Toyota hatchback might benefit from a warm guy checking its tires, a girl who, I felt, secretly dreams of a sweet guy walking her back to the car after she finishes singing in the choir, a man who will laugh with her when that beautiful throw turns into a gutter ball at the last second.

In all, at the end, I felt I knew Lars, I knew his world, and I appreciated his wonderful family and caring town. I felt good knowing that in their quirky Northern wastes they could count on each other and that love and brotherhood are always in the places where you least expect to find them.

The fact that I saw a few ladies walk out with Kleenexes proves to me that the message of the “Real Girl” is that true and abiding love we all recognize as genuine. Don’t judge this too quickly, or you may miss out on something insightful and true.