The Automat

- 4 minutes read - 681 words

- Format:

- Film

- Date Seen:

- 2022-04-10T16:00:00-04:00

- Venue:

- New Plaza Cinema

- Stars:

- ★★★★

“The Automat” is a joyous film that recalls the arrival and departure of the automatic restaurant, the automat, Horn and Hardart in Philadelphia and New York. Guided by and framed with interviews with H&H aficionado Mel Brooks, the story of a scrappy restaurant that believed in good food for the people, all people, in a beautiful environment was nostalgic, tender, and sad. As Brooks recounts: you could never make it today, it makes no sense to accounting that something so naive and good and cheap could ever be conjured again.

As we shuffled out my seat neighbor leaned over and confided: “They didn’t mention it, but the mashed potatoes were pretty darn good, too.”

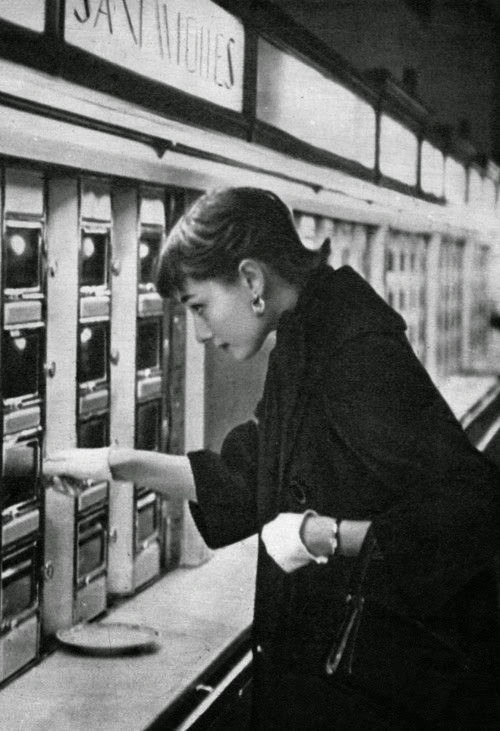

Elegance personified visited the automat

Lisa Hurwitz’s documentary reminds me, like all good documentaries and limited run series podcasts do, of the power of loving something, an idea, a typeface, a person, a TV show, a movie. Somehow, with the right amount of love, a story about a cafeteria with a gimmick becomes majestic and a symbol of America when American Ideals walked united with commercial endeavor.

The shocking (hang on to your hats) opening is that the restaurateurs Joesph Horn (of Philadelphia) and Frank Hardart wanted to bring good food to the burgeoning urban class of Philadelphia: good food at a cheap price in surroundings that were surprisingly nice. Hardart came with a passion to bring New Orleans French Pressed coffee to the North. Horn was regarded as a formal businessman, but a man who genuinely cared about people. In time their restaurants expand to New York where, it’s estimated, they were consistently feeding 10% of the population per day.

The firm’s loyalty to common people and workers that creates a portentous current throughout the runtime. Perhaps because we, as modern viewers, know that as a business this could have had bigger margins. Were it built today the tables would not be marble(!) but plastic. And were X-ray vision granted into the kitchens, it’d be minimum wage workers and peeping microwaves today not fresh-baked goods from the commissary and baked beans in small ramekins.

And just as the automat was key to offering America to anyone, regardless of class, race or ethnicity, people who went to the automat became more American. Refugees discussed the Vietnam war, in Yiddish. There’s even footage of Andy Warhol and the Velvet Undergound at an H&H. You could go beyond the avant garde, but you were never too outré for the automat.

Realizing this beauty of our country and how capital stomps it like Russian boots on sunflowers made me sad. In his New York Times review, reviewer Wesley Morris captured my feelings:

So as the millionth exterior shot and umpteenth photo of those towering cabinets hit me, I got sad, too: why oh why did it all have to end? The answer is typical: the interstate, suburbanization, mismanagement, classism, snobbery, inflation. All of which this movie does more than allude to. Source

Tender moments abound, the late Justice Ginsburg recalls doing her homework after piano lessons. Colin Powell recalls his modest family splurging to get H&H pies or go into the city. Mel Brooks recalls his brothers leaving, as they thought of it, the City of Brooklyn and going to New York where the woman, at the change desk, without looking, could take a dollar and grab 20 nickels out of a big bag.

In fact, some of the tenderest moments are Brooks talking about his friend Carl Reiner’s preferred order. And then Carl talking about Mel’s. And then Mel complaining about how cheap Carl was to not really enjoy the good stuff. And Carl complaining about how Mel was too lazy to get up early enough to know that he had already had breakfast there that morning. It’s the kind of intimacy that only good friends can have with one another — and no small part of that was apparently found over the best coffee one could ever have, for only a nickel, dispensed from taps with heads shaped like dolphins in the Trevi fountain.

Sic transit gloria mundi