The French Dispatch

- 8 minutes read - 1595 words

- Format:

- Film

- Date Seen:

- 2021-10-22T04:02:37-04:00

- Venue:

- AMC Lincoln Center

- Stars:

- ★★★

My favor for Wes Anderson movies has waxed and waned over the years: high points at Rushmore, Moonrise Kingdom, and The Grand Budapest Hotel; ebbs at The Royal Tannenbaums and The Darjeeling Limited (reviewed here as “The Darjeeling Mumbledy”). I’m glad to say that The French Dispatch joins the former set. In fact, it may well be my favorite of his films.

While still featuring his trademark flat, rectangular, composition and his

mildly obsessive celebration of twee objects (“It must be a Royal brand McBee

model portable typewriter…in putty!”), Anderson shows ever-more confidence in

his schtick style with this effort and, as a result, his actors'

performances shine and shimmer with their capabilities. He stops inserting

himself with a sledgehammer etched with the motto “DO YOU GET HOW CLEVER I AM.”

It’s a welcome mark of maturity and transition.

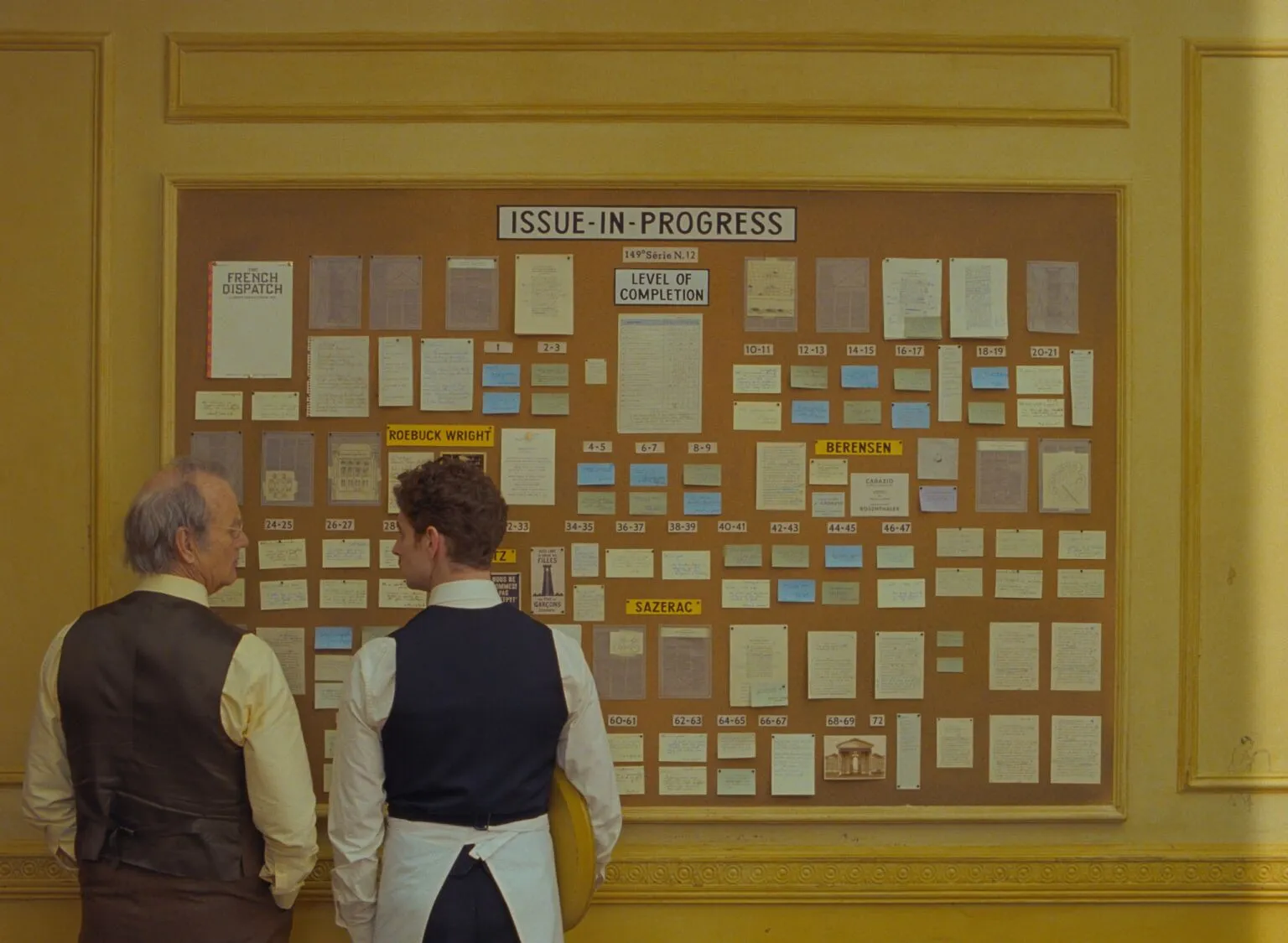

Editing be like this

With the breathing room his trust has gained him, he demonstrates nimbleness and variety. The film, composed of three primary vignettes, sees Anderson working with:

- explosive color

- editorial-grade black and white

- a gorgeous and protracted segment of nude work

- slapstick à la the Marx Brothers

- slapstick à la the Keystone Kops

- and even animation (cel-based versus stop-motion as he has dabbled in before)

The film features three core vignettes with a bonus pair serving as preamble.

First (mini-)Vignette: The Lost Son

The first serves to introduce us to The French Dispatch, a New Yorker or The Atlantic-like periodical for serious-minded, arty folks.

What’s not serious, in the least, is the naming of the characters in this film. From Bill Murray’s “Arthur Howitzer, Jr.” (presumably a wink to the Sulzberger family who runs the New York Times & the Shawn family at The New Yorker) to Owen Wilson’s “Herbsaint Sazerac” (A New Orleanian drink as surname; a given name as a wink to those who favor cannibis, presumably) to Stephen Chow’s “Lieutenant Nescaffier” (Nescafé being the ubiquitous and much-loved instant coffee of the Continent). As with most Anderson films, the characterization is solely in the interpretive hands of the actors.

The chief

In any case, the film is driven by the death of Howitzer, whose will demands

that the periodical be shut down upon his death (with the melting of the

presses, no less). The first mini-vignette is thus the story of how he, a child

of a wealthy family of New York Liberty, Kansas followed in the footsteps

of the Lost Generation to disappear into Paris Ennui-sur-Blasé,

France under the auspices of producing a magazine for the folks back

home.1

. Since I, like Howitzer, have made my home on foreign

shores and far away from whence I came, I found an odd sort of emotional

resonance with this extremely short prologue.

Second (mini-)Vignette: The Cycling Reporter

To orient the audience within the fictional setting, the second mini-vignettes is a complete crash course (pun intended, hang tight), introduction to the city by “the bicycling reporter” Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson). Wilson gamely does a few dozen man-on-the spot gags to orient us to the denizens, oddities, and arrondissements of Ennui-sur-Blasé. It recalls the list of Max’s extracurriculars from Rushmore and leverages Anderson’s trademark flat, horizontal style’s stagey appearance to do some Georges Meliès-style special effects.

‘Sazerac’ reports on bike, even from the metro

Our orientation complete, the three main vignettes er, “stories” within the Dispatch begin. Each of the three is narrated by a magazine contributor who meta-narrates their story-for-the magazine. As such, each of the three feels much more like an episode of the beloved NPR program, “Selected Shorts.”

“The Concrete Masterpiece”

‘Next slide, please’

Narrated by: J.K.L. Berenson (Tilda Swinton)

Narrated to: A rapt colloquium

The episode’s star is Tilda Swinton, aflame in red, awash in the earth tones of the 1970’s, narrating, in a wonderfully affected voice with a strange method of speaking through her front teeth a story about the latest hit of the art world: an imprisoned murderer, Moses Rosenthaler.

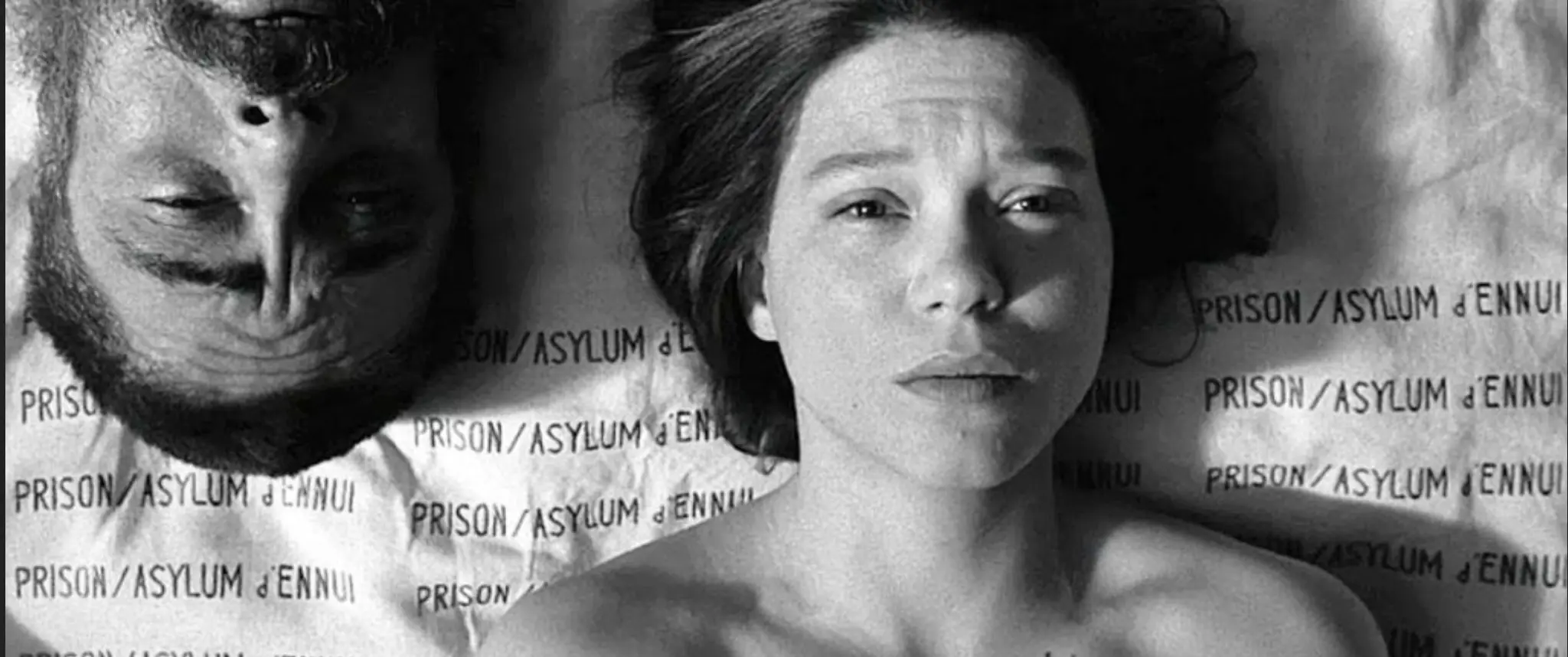

While the scenes where the radiant Swinton holds forth (with slides, a podium, and an unseen lecture hall crowd listening in rapt attention) explode with warm golden light in matching palette to Ms. Swinton herself, the depiction of the art and artistry inside the jail walls is rendered in rich Ilford photo-paper / Jules and Jim blacks and whites. Anderson revels in this chance to send-up the Goddard style with a protracted nude scene with Simone the prison gendarme (Léa Seydoux).

A more tame shot from the session

This section’s opening with Anderson-and-Rosenthaler capturing an amazing set of nudes is transcendently silent. As she’s released from her posing and releases her joints in a cathartic chiropractic cacaphony, Anderson reminds us “all of what’s natural is fake anyway, right?” I couldn’t help but feel a week to people in the audience like myself who occasionally eye-roll his precious tropes. It was a cheeky capture of the creative process.

To quote JK Simmons as “Dad” in Juno: “I didn’t think he had it in him.” Recalling iconic 1970’s French sex comedies e.g. “Cousin/Cousine:”

Aren’t we all in the prison of Ennui?

With Simone as lover, muse, and prod to Rosenthaler’s genius, their relationship is made more complex by would-be art sales kingpin Cadazio (Adrien Brody) who sees Rosenthaler’s potential as an art brand. The story lampoons the silliness of the art world (a gala opening inside of prison) and tinges the closing coda with Goddard-esque sadness. This really felt like Anderson showing his love of French cinema.

“Revisions to a Manifesto”

Objectivity

Narrated by: Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand)

Narrated to: Tellingly, no one. This character was about the work,

thankyouverymuch

The second vignette was my least-favorite. While thoroughly competent and anchored by two stellar performances by Frances McDormand and Timothée Chalamet (dude’s on a streak this month with Dune), it felt too pretentious (“reporters must remain distant and objective, except when they don’t”), too affected with the crooning, French, swoony soundtrack, and too much of a rehash of Anderson’s early-aughts effort “Moonrise Kingdom:” Two start-crossed youths find their romance blocked by the strange rules of adults and a girl has an obsession with her makeup compact.

Objectivity

I’m not sure I ever found anything to care about in this story outside the performances. It was too long and too emotionally unrewarding.

“The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner”

Moments before the gourmand-about-town tale detonates

Narrated by: Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright)

Narrated to: A 1970’s chat show (host played genially played by Liev Schrieber)

This was probably my favorite vignette. I alluded to “Selected Shorts” earlier and this vignette operates much like an episode of this dearly-loved radio programme. The narration frame is an interview with Wright (character) taking place some years after the demise of The French Dispatch. Three stories manifest in the interview. Like the first vignette, these threads converge to present gravity and insight about art and identity. The motifs are:

- Outcastness as identity

- A kidnapping

- Art and Death and Immortality

Wright tells of how he joined the periodical in a fashion that references the real-life circumstances of James Baldwin. Pushed out of America, the gay, black Wright seeks a new life in Ennui where, upon his first night in town, he finds himself caught in a sting operation against the gay bar he was patronizing. Friendless, the only phone number he knew was that of the Dispatch. Upon arriving, the Howitzer extends a job application through the bars and, impressed, pays bail and offers refuge to to the outcast before him.

Accordingly, when it comes time to consider the culinary products of the Ennui police’s most formidable and talented chef, Chef Nescaffier (Stephen Chow), for the magazine, Wright-as-outsider sees something deeper in another outsider who adopts the foreign as their home. In the midst of a “restaurants about town” article, suddenly we’re in the middle of a kidnapping that leads to an offbeat chase through Ennui that involves rappelling, animation, a strongman named Jeroboam, and has a madcap hilarity like the Keystone Kops.

In the interview, Wright recalls that after the story was written, Howitzer had pushed him to make an inclusion he had thrown out. That tossed out paragraph, rendered as a scene, is beautiful and moving. I’ll not spoil it here.

‘Howitzer’ shares an editorial moment

The upshot of the scene was that to choose death while practicing one’s art was not a mortal’s death, it was something transcendent. It recalls Nietzsche’s Zarathustra where the tightrope-walker who chose danger as his metier finds death, but also earns the immortal respect of Zarathustra for having lived authentically. It has powerful overtones for a gay, black outcast living in France (Wright); an Asian man who has learned and is a master of that most French of passions haûte cuisine; an aged American editor (“Howitzer”/Murray) publishing in self-imposed exile in France; and for his totemic presence whose obituary is the sum total of all the stories told by the writers of The French Dispatch.

Immediately after this dialogue, we pull back out a frame of narrative to see the Howitzer that this sad coda “was the best part.”

Indeed it was.

Conclusion

Against my coolness to Anderson, he really hit it out of the park with this one. I know that other films of his will be more loved and many of them have more jokes or are more accessible, but this sweet, tender, jewelry box of a stage play is now my favorite of his oeuvre.

Footnotes

- For those of use who live far from where we were brought up, this was a particularly powerful theme.