Marcy Playground: "Shapeshifter"

- 17 minutes read - 3415 wordsBackground

Released in November 1999, Marcy Playground’s second record, Shapeshifter, would never match the sales or popularity of their 1997 self-titled album. Much like other albums of this series, the previous, eponymous album had featured a once-in-a-lifetime massive hit, a “One-Hit Wonder:” Sex and Candy. Albums that produce that exceptional of a hit often set up subsequent efforts for an unfair comparison. I believe that was the case with Shapeshifter. It was a natural growth from Marcy Playground that showed positive growth and evolution, but, sadly, I don’t think it got a fair shake. The purpose of this post is to un-forget, Shapeshifter.

Predecessor

In context, Sex and Candy wasn’t wildly different than the rest of the songs on Marcy Playground. The songwriting style of John Wozniak was consistent: world-weary, historically-savvy, sweetly romantic, and a bit geeky. The guitar frequently drives the songs and shares a sonic similarity with Pixies and Nirvana (“Saint Joe on the School Bus” feels very close to “Come As You Are” washed reverb, phase-shifting and all).

One keen emergent property across the songs on Marcy Playground was the way songwriter / singer John Wozniak pushed the boundary on expressing failure and weakness in the face of the standards of (toxic) masculinity of the era. In the “Face-saving / He-man” Southern culture I grew up in, to see someone put this alternative strength through unflinching honesty forth was remarkable. For example, Wozniak bravely (and ironically) named his band after the playground on which he was regularly beat up. To hear him talk honestly about how he lived with those failures (drugs and depression) was revelatory and, I suspect, was a comfort to many boys / young men grappling with the contradictions of masculinity in its attendant code of silence. Listening to these albums again recently, I’m amazed he was willing to put so much of himself out in such a vulnerable way. Other musicians who were as unflinchingly naked e.g. Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo later went to distance themselves from such honest appraisals. Even Sex and Candy has, at its root, an anecdote about Wozniak finding safety (and, uh, sex) in the womb-like hideaway of a college girlfriend’s dorm room.

Listening to Marcy Playground again, I hear lots of David Foster Wallace themes: authenticity, resistance against patriarchy, drugs and Dungeons & Dragons as escapes from the utter bullshit of late-90’s existence.

Here are a few highlights from the first album:

- “A Cloak of Elvenkind”: A geeky loner imagines having a fabulous cloak of elvenkind (for those who have never touched a twenty-sided die, that means “made by the hands of elves”) that offers the wearer invisibility in his wardrobe behind all the trappings of masculinity that his mother sees as fit for a boy. It hits a lot of the same notes as Weezer’s In the Garage but is far less name-droppy (e.g. “X-man” Kitty Pryde, Kiss’ Ace Frehley, and TSR’s Dungeonmaster’s Guide) of the trappings of isolated geek culture

- “Sherry Fraser”: A wonderful apex of lysergically-tinted love and reminiscence about those people that we feel so strongly attached to that somehow disappear

- “Opium”: A drugged-out dream song

- “Poppies”: A jokey, jaunty, detached lark about British expeditionism changes culture by hooking us on the poppy

- “Sex and Candy”: An impressionistic reverie of post-coital daydreams (I think) with references to breakfast cereal catchphrases (“Dig it”)

- “The Vampires of New York”: A silly sign-off song about the magic and mystery of this goofy town; world-weary, detached, and so Lower East Side

With these themes and approaches as prologue, Wozniak set out to write the album that would become Shapeshifter.

Shapeshifter

Many of the themes and tropes from Marcy Playground returned, but, in the meantime, Wozniak had matured some and had even found a bit of a sense of humor. Shapeshifter acknowledged what the band had done before, but also resolutely decided to not do poppy (adjective, not noun), hipper-than-thou personal reflections.

Here, the band crossed, to my ear, the Pixies, Violent Femmes, and grunge influences with real appreciation of heavy metal progressions and rock drum work. On top of that, there’s a tad less drugs-and-suicide and a lot more humor, pop-culture, and mental reconciliation of the past. The artist’s voice has come to the black, bitter happiness of the depressive’s march where instead of leaping off the cliff, it rides a black rainbow slide back to a mediated peace with life’s absurdity and gets weird with it; to wit, “Fuck it, let’s sing about a cartoon squirrel.”

If Marcy Playground was an opiate spiral of escape and avoidance, Shapeshifter has two primary modes:

- A blithe, happy Eeyore’s birthday romp of a THC-augmented psilocybin trip in technicolor. I will refer to this theme as “Blissful Absurdity”

- A confessional arc reckoning with what had gotten our narrator into such a funk on the previous album. I will refer to this theme as “Alienation from the Dream of America.”

Additionally, most sophomore albums are also saddled with some hangover songs that didn’t quite make the cut of the previous album but which were considered “good enough” to fill out the runtime of this album. These tend to feel backward-looking or derivative. Shapeshifter is no exception. I’ll discuss these below as recommended cuts.

To this end, I’ve created my cut of Shapeshifter with the filler songs cut and the songs grouped by theme. In the not-quite-dead-yet era of the cassette, I could imagine one theme taking the Side 1 and the other, Side 2.

I’ll use this track list to talk about the themes and narrative Wozniak was working.

Also, as a caveat, it’s tempting to make Wozniak-the-person the same as Wozniak-the-Artist or Wozniak-the-Narrator. Many of the songs are written in first person with a confessional structure. To say “Wozniak says …” implies that there’s no distance between the art and the artist, the writer and the written, and that’s wrong. I’ve tried hard to be consistent and separate what I know about Wozniak-human and the narratorial voice of his songs, but it’s worth underscoring that I’m not psychologically diagnosing the artist (no qualifications for that). Rather, I am describing the psychology and emotional textures that the narrator is presenting.

The Tracks

Standout tracks are noted by ❤️

Theme: “Blissful Absurdity”

In this thematic bloc, Marcy Playground hews closer to Butthole Surfers or even “Weird” Al Yankovic by combining pop-culture with psychedelic washes.

“It’s Saturday” ❤️

Opening with a light-hearted gimmick song, the album asks us to imagine a day where a teen, in his room, decides to open the day with dropped acid and beg off of encountering society for many hours while he goes places in his mind.

It’s like a Ferris Bueller’s Day Off with LSD as the Ferrari. It’s a song that heavily depends on yodeling. This song very clearly said: “We ain’t gonna Sex and Candy this record, so let’s get that off the table right now.”

For the album, the song really does no additional work except to put a smile on your face and say: “If you expected Marcy Playground 2 forget it.” In the time, we have to remember that this was also the era of tracks like “Lump” or “Peaches” from The Presidents of the United States of America where a band could do a 3-minute song about a strange topic and get massive play on it.

“Sunday Mail” ❤️ / “Pigeon Farm” ❤️

The next two songs are freakishly absurd. The former hinges on waiting for an impossible thing (Sunday mail) and comparing it to waiting for confirmation of attraction in a nascent romance. The latter takes a blissful pride in being of the tribe of weirdos in a weird way. A “hidden track” on the CD later reprises “Pigeon Farm” in a gramophone-and-Jazz-Age rendition “Ole Pigeon Farm.”

“Secret Squirrel” ❤️

He knows he’ll always win.

This track recalls Manfred Mann’s “Snoopy versus the Red Baron” in their celebration of cartoon hero “Secret Squirrel.” Secret’s powers and derring-do are recounted in a blissful romp of a song. In the course of the song, it’s an enthusiastic tween describing the show, a bit of an interview with “Secret,” and then a malevolent interruption by Secret’s nemesis (in a perfect Thurl Ravenscroft-inspired bass):

So I see you came,

Secret Squirrel, it’s a shame

You will have to die.

Evil Cackles

In the final verse, the fourth auditory wall breaks, and we zoom out to hear the immortal Bat-quandry: “Will our hero make it out?? Tune in next week and see.”

It’s blissful stoner-grade humor lark of a song that summons chip-wood walled basements, bean bags, and half-eaten bags of Doritos.

Intermission: “Love Bug”

Back in the era when people still listened to records, this is the sort of mid-album song that creates a break before a thematic turn. It’s not bad, and the harmonizing sections are really quite good, but I’ve never found myself singing over the years (the way “Wave Motion Gun,” below or even “Pigeon Farm,” above have occasionally cropped up). Nevertheless, it serves as a pivot song between our two themes.

Theme: Alienation from the Dream of America

I understand Shapeshifter so much more by comparing it with its literary contemporary, David Foster Wallace’s massive book, Infinite Jest. In it, a world of standard-issue affluence has been paired with a high level of social isolation to create a world of ahedonia, mental illness/suicide , and addiction to media and drugs. It was a reasonable projection of “What if the 90’s is just how life will be from here on out?”

How little that question foresees 9/11, QAnon, and the gallons of blood that would be spilled in Afghanistan and Iraq. The eternal optimism and affluence of the Clinton era was not going to be a thing.

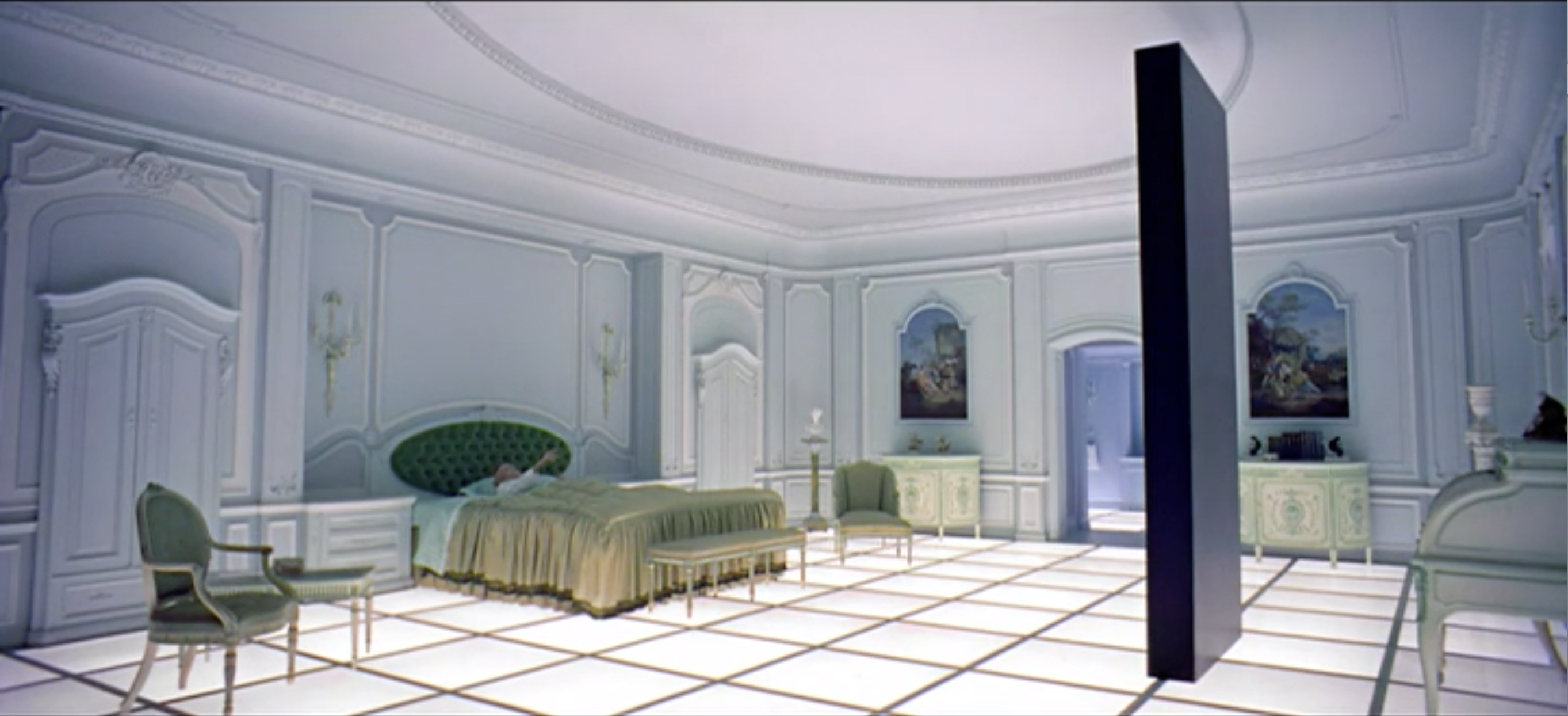

In many ways, this theme recalls Bowie’s “Space Oddity” where a Kubrickian antiseptic spacecraft, Discovery from “2001,” was the only apt metaphor to describe Bowie’s own feeling alienation from post-Nazi-stopping, war-winning English society of the early 1960’s. Few non-hardcore Bowie realize that the reason Bowie became an alien on Earth is because he was alienated on Earth. The “Dream of America” theme is something to do with material wealth beyond measure and conflicting signals about how to live life within that society. Like Bowie, authorial Wozniak can see it’s a happy time for many, but not him.

If Marcy Playground (the first album) was about living with being beaten by the impossibly sunny and positive myth of the late-90’s era, Shapeshifter’s second theme is about diagnosing the mechanics of one’s own misery in it.

“America” ❤️ / Bye Bye

I view the next two songs as confessional and thematically linked. If the outright alienation and pain that were wound through Marcy Playground were in response to something, the next two songs set up what it was.

“America’s” lyrics demonstrate that one of the reasons Sex and Candy resonated so strongly (besides S-E-X), was that Wozniak clearly has a poetic gift. In his writing, Wozniak is often detached, he’s never cynical. In Sex and Candy, that gift is deployed as an impressionistic swirl set of words to create a feeling, but in “America” I feel some of the deep poetic stirrings that “America the Beautiful” awakens. He describes the iconic view from the top of the Statue of Liberty and the mythical Pacific Northwest with its mountains and apple trees.

In this song, a series of individuals go “away” from home to iconic cities of America to find “their home.” As someone who, from about 16 onward, was feeling the pull of “away,” it was a confirmation that I wasn’t completely alone in this.

Perhaps most interestingly, the narrator, doesn’t identify with any of the cities. Instead his home is a satellite orbiting the globe à la Bowie’s Major Tom or the isolation in the final act of “2001.” I believe “America’s” narrator’s satellite follows the same path as Dave Bowman from “2001,” he winds up (in “Bye Bye”) in the Baroque rooms of Bowman on the other side of “2001’s” star gate:

…from olden times

Red velvet loveseat from olden times

There’s nobody on it but me

Everyone’s crying they’re caught up in games

Me I’m as happy as I’ve ever beenSo, bye bye my big blue marble

Bye bye my spacious black hole

Bye bye all boddhisatvasRed velvet animals swim in black tea

There’s nobody up here but me

And every mistake I make comes back to haunt me

Still I’m as happy as I’ve ever been

While the viewer of “2001” sees tragedy for Bowman alone beyond the stars, in the alienated metaphor of Bowie and the narrator, they are just as alienated as they’ve “ever been [while on Earth].”

“Wave Motion Gun” ❤️

Building on the sci-fi motif (and tropes of stoner-friendly afternoon rerun TV in the previous major theme), “Wave Motion Gun” opens with:

Backstage behind the curtain there’s an

There’s an armchair with a secret engine and you

You climb in and get naked watching “Star Blazers”Wish you had their amenities

To fend off your enemies

In one big blast from your wave motion gun

While this might seem to be another pop-culture ha-ha song, the line “[t]o fend off your enemies” hints that it’s actually about a personal frustration. While the early verses imply an Infinite Jest-like escape to a womb of private entertainment (full of cult animé and nudity), subsequent verses describe using this death beam (featured in the video game “Metroid”) to “feel like yourself again” (violence) and be where there’s “no pain again (numbness).” There’s a pair of not-so-subtle references to “shooting all your heroin” and finding the “little hole where the gas comes in [to an oven]” as methods of relief.

I believe these lines are the violent loneliness and rage of our alienated voice from “Bye Bye” frothing at the forces that made him so lonely, so isolated, and so pissed off about it. He oscillates between violence and self-immolation in a post-Nirvana Hamlet’s soliloquy. It’s the beleaguered and bullied authorial voice imagining vengeance, numbness, or death. In many ways, its delicate two verses explode outward in the final chorus pushing into a Cobain-esque scream.

Here, in 2021, it’s hard to hear these themes and not shudder at the contemporary-to-album-release high school shooting of Columbine or the genetic descendents of that event, “incels,” and QAnon. This narrator is on a bad path and (frankly) a bit more empathy toward this narrator’s voice might have helped us diagnose the metastasizing social trends that would lead to Trump supporters’ sensibility-deaf insurrection in the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

This song ends with anger. This is a voice spoiling for a fight or death and depressed enough to be eager to meet either. But the turn comes in the next song. Instead of prefiguring the path to incels and vaccine-hesitancy, something shook our narrator and resulted in his taking another path.

“All The Lights Went Out” ❤️

This song sees love rescuing the author and leverages thee writer Wozniak’s love/trust of women and his romantic side. It’s all build up to a lover’s whisper about their private sanctuary:

“What if our love could blow a fuse in Heaven”

and then:

“Today, all the lights went out in Heaven.”

which implies that the fuse was indeed blown. For someone who suffered grimly at the hands of masculinity (both the factual Wozniak and Wozniak-as-narrator of the songs of this theme), the feminine was a safe retreat (Sex and Candy) and submission into it was, for the narrator, a key for accessing the sublime.

The song leverages the quiet acoustic aspect of the band’s capabilities and a subtle whisper of the lyrics before there’s a dramatic sonic shift to power chords, drums, pedals, and volume. It’s like the sound of a rupture in space-time as the narrator’s third eye opens and multicolour mandalas of human bliss unfurl. I think this song is the hint that the author’s seen a way out of alienation: love and all of its higher actions, forgiveness and understanding are going to liberate him from the chains of anger and humiliation (and they do).

“Our Generation” ❤️

If the furious voice of “Wave Motion Gun” has perceived enlightenment after “All The Lights Went Out,” the final song is doing the hard adult work of facing trauma and moving beyond it. Our narrator is honest, reflective, and pensive in trying to understand how the system managed to make the angry him he used to be.

In some ways, I think this song is the most important for understanding Wozniak-the-man as a writer. He was a part of the Marlo Thomas-inspired “Free to be You and Me” generation and he got is ass kicked for it, repeatedly, on the dirt of Marcy Playground. That experience left him a bit confused and hurt: drugs, depression, and his art were all the fruits of that mixed message: “Free to be you and me…but you best not be too free lest you get pummeled.”

If the first album was inspired by living through that contradiction, and “Side 1” of Shapeshifter was recognizing that everything was an absurd mess because of it, “Our Generation,” like Infinite Jest, functions as a plea for a return to earnestness. The narrator seems to be done with his detachment and seems to suggest that he’ll start out on a new path by being honest to his tormentors and acolytes alike:

I am a child of the free-to-be-you-and-me generation

and I am with you

in being confused.

Maybe his bullies were also victims of someone else somewhere else. Maybe the drugs and the anomie and ahedonia aren’t necessary aspects of life. This voice sounds like one that has profound empathy for the world, and even for itself. It’s a Clintonian coda: maybe we can beat the “Inconvenient Truth” that we’re destroying this blue marble “whizzing through space;” maybe this new “Internet” will connect us and stitch together rifts from the past (“there’s nothin’ to it!”) I like to imagine the narrator is willing to put his pain and rage in the past and start moving to something different. It set me up for great excitement around what their third album would sound like as it was the last song in the released version of the album.

Songs to Cut

Rebel Sodville

This is my least favorite song. It feels a lot like the ideas that The Decemberists would get right on Picaresque.

It’s somewhere between the Threepenny Opera and the Italian adventures section of The Count of Monte Cristo. The lumbering song describes the court of a picaresque (thief-?)king and his attendants. It seems to lean heavily on musical motifs already used in the previous album and, to my ear, it never quite gels. It’s another song where the Dungeons & Dragons background Wozniak must have had suggests itself, but it never quite moves, uplifts, engages, or humors strongly enough to really engage me. I usually skip it.

I wonder whether there was a plan to do a multi-song mythos arc about Sodville in there? That might have been interesting, but I feel no joy in this number. It feels like a leftover from the Marcy Playground sessions that was crammed in as it has home neither with lysergic bliss or the challenges of alienation.

“Never”

Ugh. It’s like landing in “Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf.” It feels like we’re in the middle of some dysfunctional couple’s argument in a Target parking lot.

Reception

Obviously, Shapeshifter didn’t have a Sex and Candy, and for this sin MP were to be pushed out of the loving arms of major label support. Its performance was not the sort of things record companies facing the existential threat of file-sharing tidal wave could bear. It’s humorous to note that their third album, “MP3,” has a coy double-meaning: either the factual “Marcy Playground 3” or the name of the file format that was killing the record industry. I can’t help but see some glee on the band’s part there.

In any case, Marcy Playground spent the subsequent years honing songs on their own and releasing through smaller labels. Three more albums would find their way to release via indie means. After years of lost recordings (due to floods!) and the ups-and-downs native to life, the crew have, of late, been touring on alterna-rock bills (poor things have to close with Sex and Candy every show, I’m sure) and will play NYC in September 2021.