My 2025 Obsession: NeXTSTEP, OpenStep, and NEXTSPACE

- 2 minutes read - 387 wordsYeah, so it’s been a minute since I’ve written. With a toddler, marriage, work, etc. my tiny little bits of free time have forced me to choose between blogging or Doing the Thing. Let me tell you about the Thing I Did.

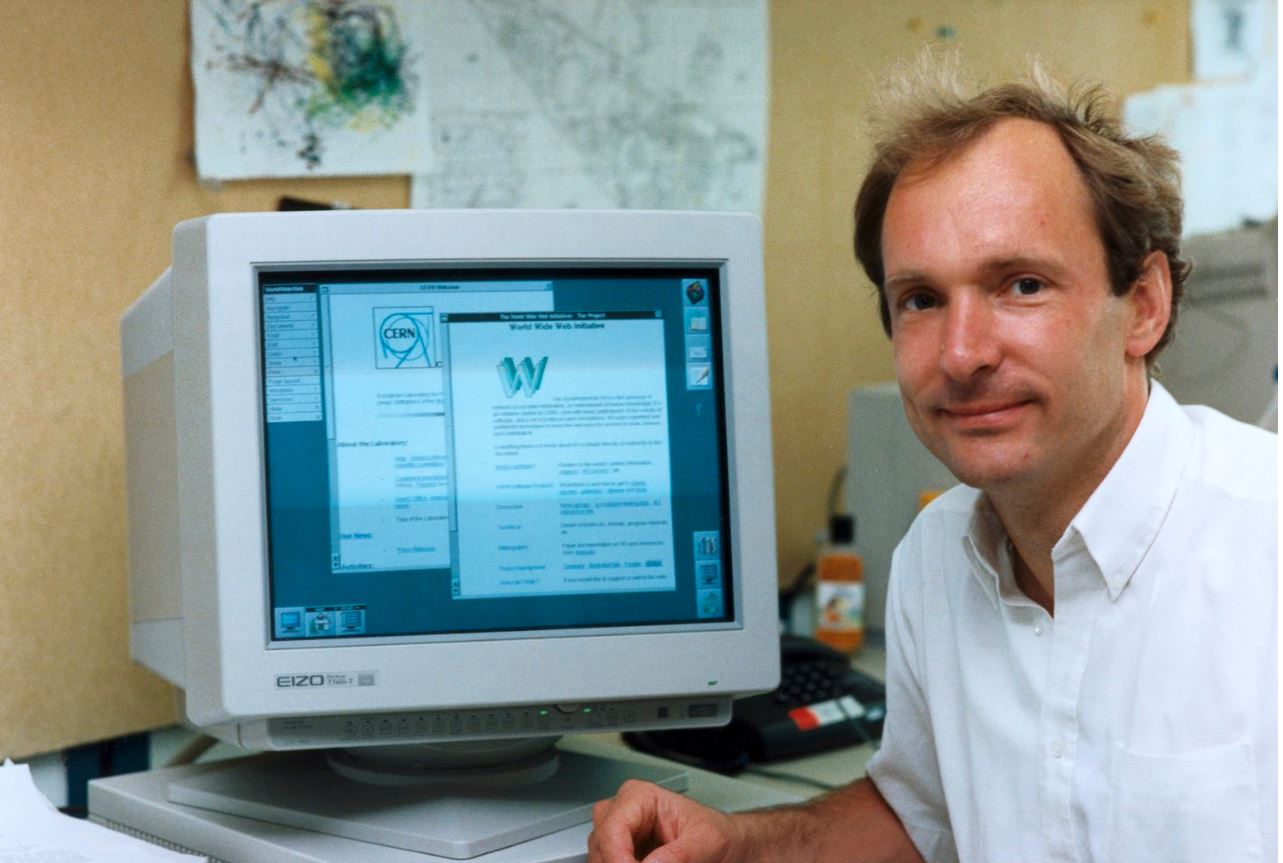

I ported Sergeii’s NEXTSPACE project from Linux to FreeBSD—the operating system of my “Just Focus” laptop. NEXTSPACE recreates the NeXTSTEP desktop environment, that gorgeous UI from Steve Jobs’ NeXT computers. On top of this, I integrated GNUstep, the Free Objective-C development environment and graphical interface builder modeled on NeXTSTEP. This crisp UI and insightful programming environment were so elegant and ahead of their time that Apple would build OSX (now MacOS) on it. There’s a reason Sir Tim invented the World Wide Web on this platform.

A beautiful desktop and an elegant programming environment, together about to unleash Babel 2.0

While I’d been too young in 1989 to know about NeXT, I sought to re-create what John Perry Barlow described in my favorite episode of “This American Life #74: Conventions”:

the only computers…where the whole notion of design was really important to the product—elegance of design.

Or prove myself to be proudly part of that cohort of individuals named by Barlow as “Unix weenies by Armani.”

Right before the end of 2025 I finished my proof of concept. It worked. I’ve made a few improvements since then and have chased down some battery-burning inefficiencies. In fact, I’m using it right now.

And along the way, I worked with AI through the development. My C is far too primitive, my Objective-C too narrow to deliver this beast of a project. So the success here suggests a certain type of success for AI-assisted development, in this case with Claude and later Claude Code. Some of my experiences suggest the positive case for AI that I hope critics can earnestly engage with.

Ultimately, succeeding in The Thing didn’t leave much time for blogging. Until now. I’m going to break this story into:

- This introduction

- A description of the coding work and in particular how I used AI while doing it

- A reflection on the positive use cases for AI based on this experience

Continue reading: Part 2 covers the seven-phase technical journey of porting NEXTSPACE to FreeBSD, and Part 3 reflects on the positive case for AI-assisted development.