The Life and Times of Schoolgirl Maud Fenstermaker

- 8 minutes read - 1503 wordsOut on a sparsely populated prairie, there once was a girl called herself “Maud Fenstermaker.” The daughter of Germanic immigrants, she grew up in Basil, Ohio, a village that no longer exists. As a girl, she studied grammar from Reed & Kellogg’s Graded Lessons in English Grammar. One day, perhaps idly passing a dull school-day, she recalled a bit of a verse from a poem from an annual reader for children called “Chatterbox.” In pencil, she wrote down a couplet, misremembered as a quatrain, onto the flyleaf of her grammar book. On another Fall day, she wrote out her name and the date in confident Copperplate strokes, recording her name and the date: October Copperplate strokes, recording her name and the date: October 14th 1891. On another day, with another ink, she seems to have revisited her signature and made a few delicate adjustments.

One hundred-and-twenty-five years later, I bought her grammar book and began pulling at the thread of this life that ended before my own began. I’d like to share what I know about Maud(e) or Mathilda thanks to the internet. In her story I found a story of America and Americanness.

Note: Storytelling based on genealogy is a series of likely guesses. Is it possible the writing was done by Maud’s mother, sibling, or teacher? Possibly. Was it possible her name was Maude versus Maud? Possible as well. Spellings, especially in immigrant communities, were famously changeable as literacy and Americanization worked their effects. Accept this as a work of speculative historical fiction.

This is the problem of history. We cannot know that which we were not there to see and hear and experience for ourselves. We must rely upon the words of others. — Yaa Gyasi

Maud’s grammar book’s flyleaf

The Book

Between a general interest in linguistics, being a programmer, and a study of Latin, I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for the turn-of-the- 20th-century grammar or secretarial reference books and their pedagogical method.1.

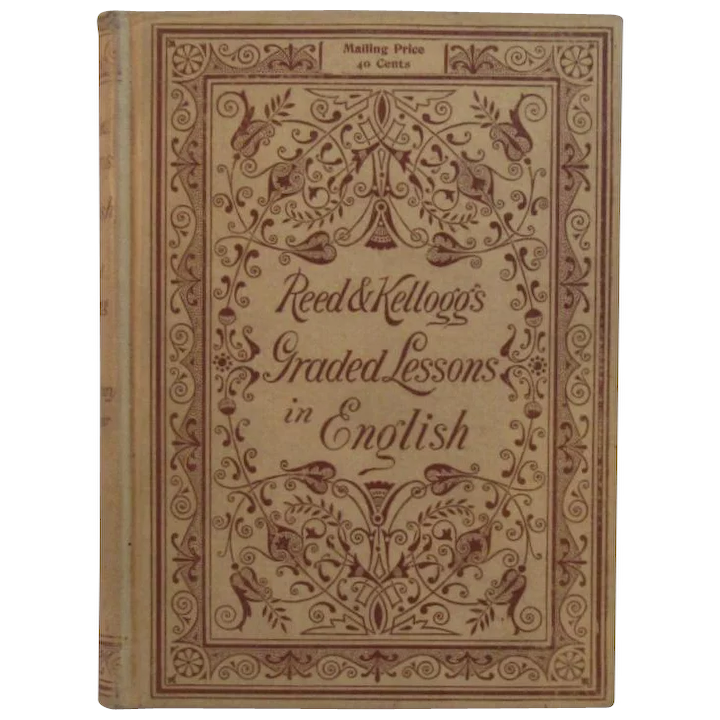

In their construction, they tended to lean heavily on rote memorization, repetition, and an axiomatic presentation of precepts built upon one another in the venerable style of Euclid’s Elements.2 Books of this type that I know are Allen & Greenough’s Latin Grammar (1904), Gregg’s Shorthand (1888), and Reed & Kellogg’s Graded Lessons in English (1892).

Lately I’ve been studying and have been creating a method for breaking down grammatical units for purposes of translation / grammatical analysis and this has lead me inevitably to research the abstraction known as the “sentence diagram” and its concomitant activity of “sentence diagramming.3” The book that brought sentence diagramming to the world was Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg’s Graded Lessons in English.

Here, “graded” refers to Latin “gradior” as in" gradation," “graduation,” etc. — a line of progress of increasing difficulty. The book itself was conceived by these two scholars during their tenures at the Brooklyn Polytechnic institute. Located near the modern the modern City Hall / Brooklyn Law School area near Jay Street in Brooklyn, it was a college-preparatory academy for the sons of wealthy Brooklynites. Later, it moved from university-preparation to being a university itself and was the home of a number of important discoveries in the 20th century concerning radar and aerospace.

I decided I wanted to have a copy of Graded Lessons in English. This being the 21st century, I found an antique copy for sale on Etsy. The cover is a work of art. It appears to be letterpressed into cloth:

When I found a copy that I wanted to buy, the seller had included a few interior pages, including the flyleaf. And that’s where my mystery began. There were a few striking things to start:

- The date: 1891

- The date: 1891

- The town, Basil, Ohio

- The name, “Maud Fenstermaker”

- A faded bit of penciled verse

- Stickers (pasted or taped in; probably not the work of the original Miss Fenstermaker)

I decided to find out more abut this person from a century ago, her life, and her times.

The Scene: Ohio, 1891

Taking a look on a modern Google map, one quickly finds that there is no Basil, Ohio anymore. Fortunately a history of Baltimore, Ohio tells the story of three nearby villages: New Market, Basil, and Rome all converging into one as the Ohio-Erie canal slowly came through their community.

New Market was home to Virginian transplants. Basil was a misspelled version of Basel, the Swiss city. Apparently hamlet pride was known to turn violent (!) between these two as the Swiss-Americans thought the Virginians too wild; the Virginians thought the Swiss-Americans dumb. A few years later the hamlet of Rome was established to the north of these villages. They were eventually incorporated into one municipality around the end of the 1940’s called Baltimore. In the late 1800’s, Maud’s time, Basil existed as the “Swiss” city of the East side of the PawPaw Creek Valley in Fairfield County, Ohio.

At that time the population of Ohio was something on the order of 3.5 million. James Garfield had been assassinated not yet a decade gone by and a Hoosier Senator, Benjamin Harrison, worked in a Washington D.C. a mere quarter-century from the end of the Civil War.

The Fenstermakers

Aligning with the Swiss heritage of the area, it makes sense that the Fenstermakers were Germanic. Fenstermaker is an English translation of Fenstermacher which means “window-maker.” The knowledge of glazing and framing were significant enough that the trade-name was a commonly adopted surname among German immigrants. Because of the difficulty of making windows, those who practiced this trade were usually paid better and carried a hint of prestige. This explains the prestige of it becoming one’s surname.

Here on the Ohio prairie, though, it seems the Fenstermachers-become-Fenstermakers were farmers, like most of their neighbors in this countryside. In Franklin County, they were something akin to a founding family with patriarch Samuel having numerous children including a “Maud E. Fenstermaker” who, in 1890-1891 would have been around sixteen to seventeen years old. This would be old enough to have mastered a difficult pen-hand with her dip-pen, but young enough to record a bit of verse from a not-too-distant childhood on the flyleaf.

I suspect this book was held by Maud(e) Estelle Fenstermaker as she finished her studies. By the 1900 census, “Maude Whims” appears alive and well as a wife and homemaker to her farmer husband.

It’s reasonable to guess that Miss Fenstermaker might have been one of the first students to attend the school where the Viriginians of New Market and the Swiss of Basil first started learning together. With exposure and co-education, the towns’ boundaries blended and the PawPaw’s division was largely erased.

I’ve intentionally only skimmed the top layer of genealogical history here. My curiosity was satisfied to know who it was who learned from this book, where she was from, and what became of the lady. Further genealogical research was beyond my scope.

The Verse

In pencil, on the top of the flyleaf is the following verse:

Come back, she cried,

when you are king,

And better roses

I shall bring!

Searching for this, I found these lines in a bit of verse about Bonny Prince Charlie’s visit to a Scottish village. The poem appeared in an English annual reader called “Chatterbox” which was punished for about 50 years from the 1860’s into the 1920’s

Published by Rev. John Erskine Clarke, the annuals provided distraction and amusement for children (and the relief of parents) founded in manners, kindliness, sociability and other Victorian morals. Leafing through some of the samples, it’s no more unusual to find a story about the visit of a failed pretender to the English crown than a quote from Ecclesiastes or a fable or an admonishment to proper manners.

The Stickers

I can’t make out whether the images are taped in or drawn in. They seem to be images that are taped in, so I’m going to presume they were a subsequent addendum.

Conclusion

So concludes the mystery and the trip across history. In a few days time I’ll have an antique book of grammar and a young lady from the Ohio prairie’s possession will become mine. Who ever could have imagined our lives could have crossed and that she’d have filled my day with imagination?

Footnotes

- This probably merits a fuller post at some time

- The efficacy of this style of writing is, courtesy of modern psychometry and learning science studies, highly in doubt and is no longer widely supported. Before these scientific approaches to learning, though, like the rote method, texts such as these were the norm.

- In what’s becoming a theme, the efficacy of sentence diagramming as a means for teaching grammar is also, unsurprisingly no longer taught or supported by various instructional councils. While the research I’ve read around learning science is compelling (“Teaching abstractions to those who don’t understand the concrete is inefficacious”), to have a vocabulary for and appreciation of describing sentences’ parts' functions precisely remains oddly engaging for me.