Revisiting Dark Souls and Nietzschean Philosophy

- 12 minutes read - 2400 wordsRevisit: I’ve always felt like I didn’t quite get the original post on this topic quite right. So I’m revisiting!

Spoiler Warning: Light spoilers in the introduction. Full spoilers past the jump.

For Valentine’s day 2017, Lauren bought me a PlayStation 4 and “Dark Souls 3,” From Software’s final offering in the “Souls” universe and, at the time, the game to get for the platform. It follows the standard design of taking the D&D that I used to use polyhedral dice for, wraps it in amazing graphics, and sets it in an expansive, fantastical, and labyrinthine world.

As I played (and re-played) the game, I saw many elements of Nietzschean philosophy surface that I kept mulling even after I’d finished. Months later, I contend that “Dark Souls” is a narrative exploration of Nietzsche’s “Last Man” thought experiment.* I’d like to record how and why here.

For more about Nietzsche’s presence in “Dark Souls” read on…

“Souls” Culture

“Souls” fans are committed. They master the game’s complex mechanics and learn to best the punishing bosses. They also trade insights and theories ad infinitum about the lore of the game. In their hands, the merest morsel of connective narrative tissue can be spun into rich theories and side-narratives.

For these fans, the fights, the weapons, the choices, and your interaction with non-player characters deepen the rich world of “Souls.” Many regard the creator of the series, Miyazake, as something akin to an auteur like Goddard. Through Miyazake’s work we are given a psychological, social, and philosophical outlook. Consider “Vaati Vidya” who has created scores of videos theorizing about the “Souls” universe. This is hours of beautifully-produced content that explores the barest scraps of primary source. It’s like watching shows about the Dead Sea Scrolls or the building of the pyramids. From little found, much is mused.

The Nietzschean Proposition

Much like in Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, Miyazake’s “Souls” is set on a stage built of myth. Both authors look at what happens when valor-based, virtue-ethics-oriented society ceases adhering to the celebration of the striver and instead comes to honor predictability and a petite bourgeoisie type of burgher society. Ultimately both authors find seeds of degeneracy in the ancestral mythic era and let that degeneracy play out fully before setting a naif loose as eyes and ears to relate what this world is like. Our naif, having grown wise in his travels inescapably comes face-to-face with the critical responsibility of the Ubermensch:

Is it more correct to consciously end a kingdom in degeneracy or to renew it, even while knowing that by preserving the carcass upon which buzzards feed, more misery and exploitation will come of it (false prophets, snake-oil salesmen, and warlords).

Let’s examine “Souls’” mythic foundation.

Game Background

Dark Souls is Hard

I realize (now) that it took me weeks to get through what was, likely intended to be, a 1-day jaunt. Nevertheless, “Souls” is renowned for its difficulty. I’m not entirely sure what this has to do with the myth, but somehow the level of struggle provides a special payoff as bosses are beaten but also lore is given.

Dark Souls is Coy

There’s little-to-no framing narrative. For some strange reason your only smattering of back story is that you know the primordial “first fire” is fading (the life force of the magical reality of the game), pilgrims are dying en route to some place, and powerful beings are also awakening from graves but are refusing to save the world. Go play!

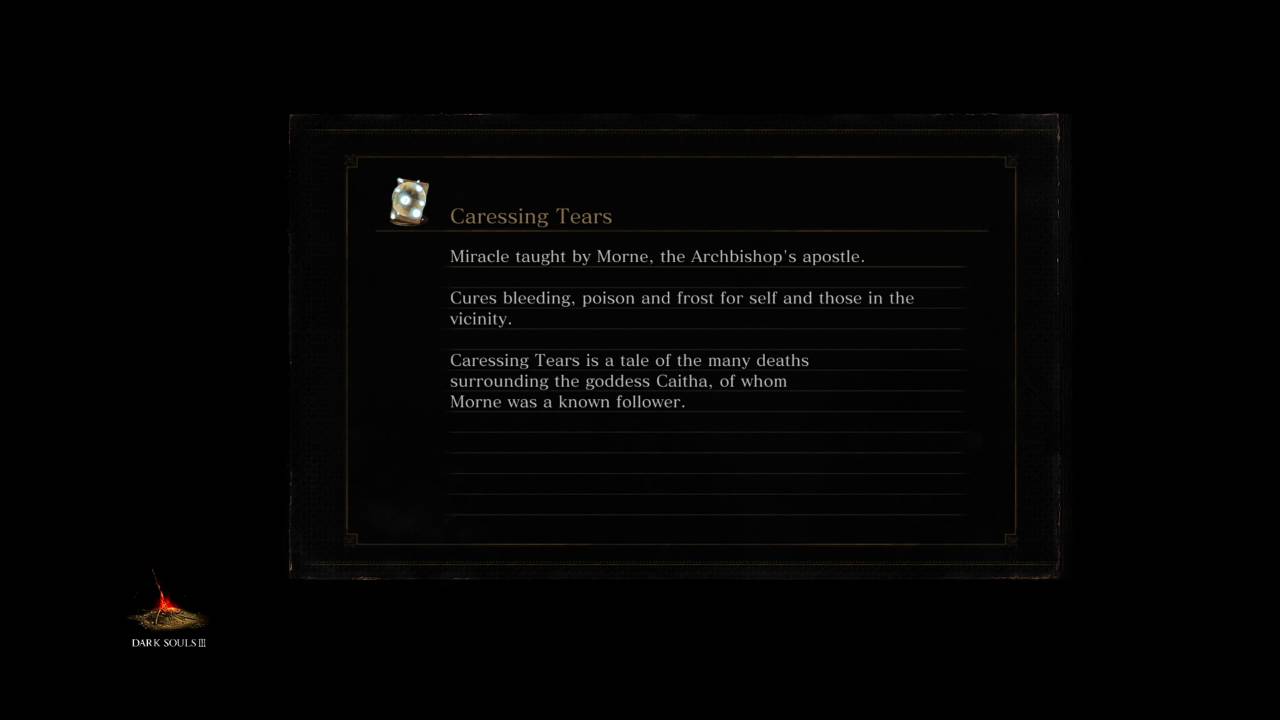

Tantalizingly, when your game loads, you’re given a title card with information about an item, its provenance, its wearer, and occasionally its lore. Sure it’s nice to learn about (say) lightning arrows; but, when gaining a lightning arrow we learn of their use against dragons in a great war of the past.

As an example, here’s the information on a miracle (like a spell) called “Caressing Tears.” And no, you have just as much information as most people do when you read this.

The game starts with you holding but a few plot shards and doing so keeps your eyes primed for clues like statues, paintings, title-cards, dialog that fill in the why you’re here or what has happened. It serves as an enticement but also as a means to help create a feeling of age, grandeur and mythical gravity from very early on.

Dark Souls has a Creation Myth

The “Souls” franchise hinges on a creation myth that recalls Empedocles' Schopenhauerian creation myth or Schopenhauer’s biological Will. The world was ruled by immortal dragons and ancient trees and then Disparity (strong Empedocles) emerges, creating light and dark, heat and fire. From the dark, bodies shuffle to the fire and it in find great souls (“Lordsouls”) aligning to 3 fundamental aspects of existence:

- Gwyn a Sky-titan, lord of Sunlight and Lightning à la Zeus and his knights who fight to instill order and establish a feudal-style kingdom

- The Witch of Izalith a goddess of Fire and her daughters, whose followers master fire-magic (“pyromancy”)

- Gravelord Nito, a god of disease and dark sorcery; also, the god of death

But then in the darkness a creature called the “furtive pygmy” — man, scrounges in the flame and finds the Dark Soul. It is a tiny soul, not full of power like the other lords’ souls, but infinitely shareable. For when a lord gives a piece of his soul away he grows weaker. When the Dark Soul is passed, it remains identical but increased. With enough desire and Dark Souls, Gwyn’s monarchy built on Lord Souls could be undone. For this, Gwyn fears the keepers of the Dark Soul. Here Gwyn is similar to Kronos or Zeus.

The Impact of the Myths

First, “Lord-Beings” i.e. bearers of finite, but powerful Lord-Souls are in an uneasy relationship to lesser beings each with an undilutable but “tiny” Dark Soul. Consequently these Lord-Beings (or gods) are both worthy of veneration but also prone to vanity, cowardice, and feats of genocide or brainwashing in order to maintain their control. In doing so, they instill a culture of vacuous veneration and learned helplessness.

I find this tension hugely compelling myth-building because there is something to man: weak though we are, prey that we are for stronger beings, there’s something in our number, the ease with which we draw short lives to our dust and loose it again betrays a hidden and subtle power behind our brief existences. It’s that power that’s unleashed in the “intercision” of the His Dark Materials universe. It’s the subtly moving dialog from a recent season of “The Good Place” where Eleanor, when speaking to a supernatural being says:

All humans are aware of death. So… we’re all a little bit sad…[It’s a bad deal] but we don’t get offered any other ones. And if you try to ignore your sadness, it just ends up leaking out of you anyway. I’ve been there - everybody’s been there. So don’t fight it.

Our power against the mightiest sky-gods is our uniquely powerful sadness fueled by our short lives. And this is a beauty.

Second, the apex Lord-Beings have died (or been slain), so the original lieutenants of the realm now steward using their tiny shards of their fractions of Lord-Beings’ gifted souls. The Lord-Beings’ toadies are running the show in the Lord-Beings’ names, but not to the same standard.

If the original Lord-Beings were vain and possessive, those who did not directly vie for the original souls are more so as they have to cover up for the fact that they’re illegitimate caretakers in the steads of their betters.

Third, weakness, vanity, and sloth multiply with arrogance as those lesser-lords enlist hordes of worshipful humans to uphold their bureaucracies, claims, and legends. The oppressed, the depressed, the delusional, and the insane all apply themselves heart and, ahem, soul to these empty veneration acts in effort to re-connect with the greatness of the passed ages of glory.

By the time of Dark Souls 3, we’re in a tin age where those devoid of soul or purpose (literally, called Hollows) roam this weary, wheezing world awaiting an external redeemer…or destructor.

Through this game arc, we are in a living example of the world of Nietzsche’s Last Man. The denizens are those who, lacking any spark of genuine Will to Power feast on the world’s carcass, preferring comfort and hollow existence to the heroic effort that conquest, or destruction would require. It’s a world of dull, sunlit stasis. In palette and sound it recalls T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”.

The eyes are not here

There are no eyes here

In this valley of dying stars

In this hollow valley

This broken jaw of our lost kingdomsIn this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of this tumid riverSightless, unless

The eyes reappear

As the perpetual star

Multifoliate rose

Of death’s twilight kingdom

The hope only

Of empty men.

We see a repetition of other key cyclical mythological ideas:

In this corrupted mythic world, at this point in its history, Dark Souls asks us to make a choice for it: Preserve it, Conquer it, or Destroy it.

The Decision of the Unkindled Ash

Through the opening of Dark Souls 3, we learn that the resurrected God-beings were supposed to nourish the first flame and again renew the world in a self-sacrificial act. The character that we play in Dark Souls 1 performs the second re-kindling. In that game, we played the hero: redeeming the Lord-Being (Sky-God) Gwyn’s Golden age, but perhaps ever-so-slightly less Golden. It’s a simple knight-errant geste.

Here, in Dark Souls 3, after unknowably many re-kindlings, the world is grown weary and seems to have grown ever weaker after each re-kindling. It’s a much more interesting proposition to the player especially since those who are supposed to redeem the world (as we did in the first game of the series) have chosen to abandon this duty. Here are their motivations:

- One has sunk into a depression and remains a shut-in to the consequences of his successful rekindling; he inadvertently killed the humans of his kingdom (Yhorm the Giant)

- Another returns to a self-pleasuring orgy of consumption: slowly, inexorably devouring all life from the greatest souls to the weakest in a slow, but certain quest to consume all life itself (Aldrich of the Deep)

- Another returns to a hollow cult of fighting; a distraction (Abyss Watchers)

- Another resigns himself to inaction, consciously choosing to watch the death of the world (Prince Lothric)

With these “Lords of Cinder” choosing to abandon their (seemingly) heroic duty, the mechanics of the world raise our character from the grave. The puniest, the weakest, the least-capable is to judge these “betters” and the world’s fate.

This joins the unique nature of the Dark Soul beautifully. At the end, the Least shall render the ultimate verdict on the world of the Great.

In the gameplay, we slay each of the Lords of Cinder so that our resurrected human might perform the final act, killing the primordial guardian of the flame to earn the claim to the Nietzschean choice:

Do we sustain, rule, or end this gasping, corrupted world and its wheezing motor? Depending on certain choices made in game, we earn several possible endings:

“Heroic” Ending

The game and conventional RPG meta-narrative sets us to believe that to refuse the call to re-kindle is an act of cowardice or dereliction. However, as we traverse the world we see a world populated by Nietzsche’s “The Last Men.” The pious are ruled by a warlord (Pontiff Sulyvahn). Those with any sense left (not fully “hollow”) dwell performing their own coaxing “loops” and being proselytized to by the warlord’s profane “religion.” By the end, we wonder whether this is a world worth saving. Suddenly the most heroic act seems much more complicated to identify.

Should the player choose this ending the great flame rekindles, but it’s too weak to re-energize the world. Instead it rests like an aura on the player. The sacrifice didn’t save the day. The flame still fades.

“Cynical” Ending

Another game sets us up as the dupe of another religion. The religion flatters and beguiles with “love,” but ultimately it is a ruse to sink us into the religion’s morasses. If we’ve followed this path, we become the new iron ruler, but ruling in the name of the church of the Dark Soul. Another weary world, another weary boss. We can project that it won’t be long until another warrior comes to fell us.

This is called the “Lord of Hollows” ending.

“Death” Ending

The last ending is to choose to extinguish the flame, to betray your sacred mission because you’ve realized that both the mission and the sanctifying authorities are corrupt. Through a set of almost easter-egg-ish-ly bizaare operations, the player learns that they can extinguish the flame, can bring a true end to the cycle of sacrifice and re-kindling.

Conclusion

Ultimately Dark Souls give us such a difficult and challenging and mythologically rich world in order to give us real stakes when we face this question as a newly-ascended power-being. Freshly made most-powerful, can we bear the terrible weight of choosing to end the world or are we so tied to the tired hero-narratives that we’ll do the “heroic” thing even when that heroism is highly questionable?

It’s a fascinating question that requires curiosity and weighing (and re-weighing) the lore-bound evidence. But, like any good work, Miyazake’s questions are “big ones” that leave us with phenomenally rich explorations.

In my view, given creator Miyazake’s statement that this is to be the last “Souls” game, the “best” ending is the ending where we put all charades to an end. We free all souls from bearing the burden of existing in this corrupt world. We close the books, turn out the lights, lock the door and simply end. In this we are the Ubermensch, realizing the fundamental degeneracy and judging it corrupt, we make the decision of a God and live with that awesome power and that awesome burden.

Footnotes

- *: I use the translation of the “Last Man” as the “Last Race.” The singular mann is symbolic of the whole race. Given that Souls features more races than actual men, I wish to emphasize “All being in this world.”