House of Leaves' Subtle Easter Eggs

- 6 minutes read - 1149 wordsIntroduction

In 2000, Mark Z. Danielewski published House of Leaves. While ostensibly a genre novel (horror), the book is much more than that owing largely to its conceit, or if less kind, gimmick, that

- there is a principal narrative reflected in a film called The Navidson Record

- that is presented as the subject of a number of scholarly analyses

- which were incompletely collected by a character who is dead

- but which are arranged to completion by an unreliable narrator

- who annotates the collection with his feelings about the action in a series of discursive footnotes (his name is “Johnny Truant”)

- which are collected by an editor who reviewed Mr. Truant’s work

- which is read by you

- which is also read and destroyed by a character in the principal narrative (and thus the ouroboros is sated)

In such a multi-layered tapestry there are many interesting discoveries and connections, to be discovered and House of Leaves has sprung a cottage industry of fan-theorists and analysis. I think I have found an “easter egg” hidden by Danielweski for those familiar with Latin and, specifically Ovid, that I’d like to point out.

SPOILERS: It should be obvious that there will be some spoiler potential after the jump.

Layout

As mentioned, Danielewski presents a number of narrative “frames” at the same time in the book. To support the reader in keeping these voices, commentaries and meta-commentaries clear, Danielewski uses the book’s layout and typesetting to drop breadcrumbs for the reader guiding the way to which narrative “frame” is being explored. For example, as a character goes through a narrow passage, the margins grow tighter and tighter while using the typeface of the innermost frame.

Danielewski, who did much of the layout design himself, uses layout as a tool for communicating the action and mood of the characters just as he does with his word choice, etc.

The Horror

The easter egg is set near the beginning of the work. The reader has recently joined two relocated urbanites Will Navidson (photojournalist) and Karen Green (former model and mother to their two children) as they pursue that fabled flight from urbanism and its concomitant workaholism, ease of access to ex-lovers, and grime to a quiet, rural Virginian home. But there’s something wrong with this home, and it starts with only the smallest, slightest problem: the house is a mere fraction of an inch longer when measured from inside than it is when measured from without[1].

While the prospect of addition and geometry no longer working may seem to be a relatively un-adrenalizing horror compared to a zombie or demon-driven psychopath with a chainsaw, it is, in fact, a supremely unsettling horror. Kant wrote that the experience of space and time as ordered axes are so vital that no experience could be meaningfully discussed without having them as the base frame[2] for discussion ("a priori intuitions"). What would it mean to have those special preconditions for experience be brought into doubt in a way that “while not exactly sinister or even threatening…[destroys] any sense of security or well-being (p. 28).”

Facing the Horror

Will, an agent of [agon][agon], and hewer to of the macho, heterosexual male ur-myth, steps forth and attempts to conquer the offset by works of arms: laser tape measures, compasses, blueprints, second and third opinions.

Karen enlists a friend to help her seduce the monstrous House. They “fit” pine boards to a wall so that, when bounded by the two perpendicular walls, the plank creates a bookshelf. She lades the shelf with her books: pulpy collections of poetry and photos. She asks the lion to sit like a good kitty at her tea party and for a while it complies, bemusedly, bearing “her books…her ’newly found day to day comfort’ (p. 34)[3].”

And then the beast snaps its jaws: a visitor bumps the row of books on the

bookshelf and the book at the end falls off: more space has suddenly appeared

such that the “bookshelf” has become a plank that seems to have been cut too

short to fill the space, a novice carpenter’s error. Inconceivably, the wall

has grown. The House’s indifference to spatial truth, a necessary truth, a

truth as essential as 2 + 3 producing 5 or cogito ergo sum, is cruelly

hurled at Karen as the chapter ends. She screams.

The Easter Egg

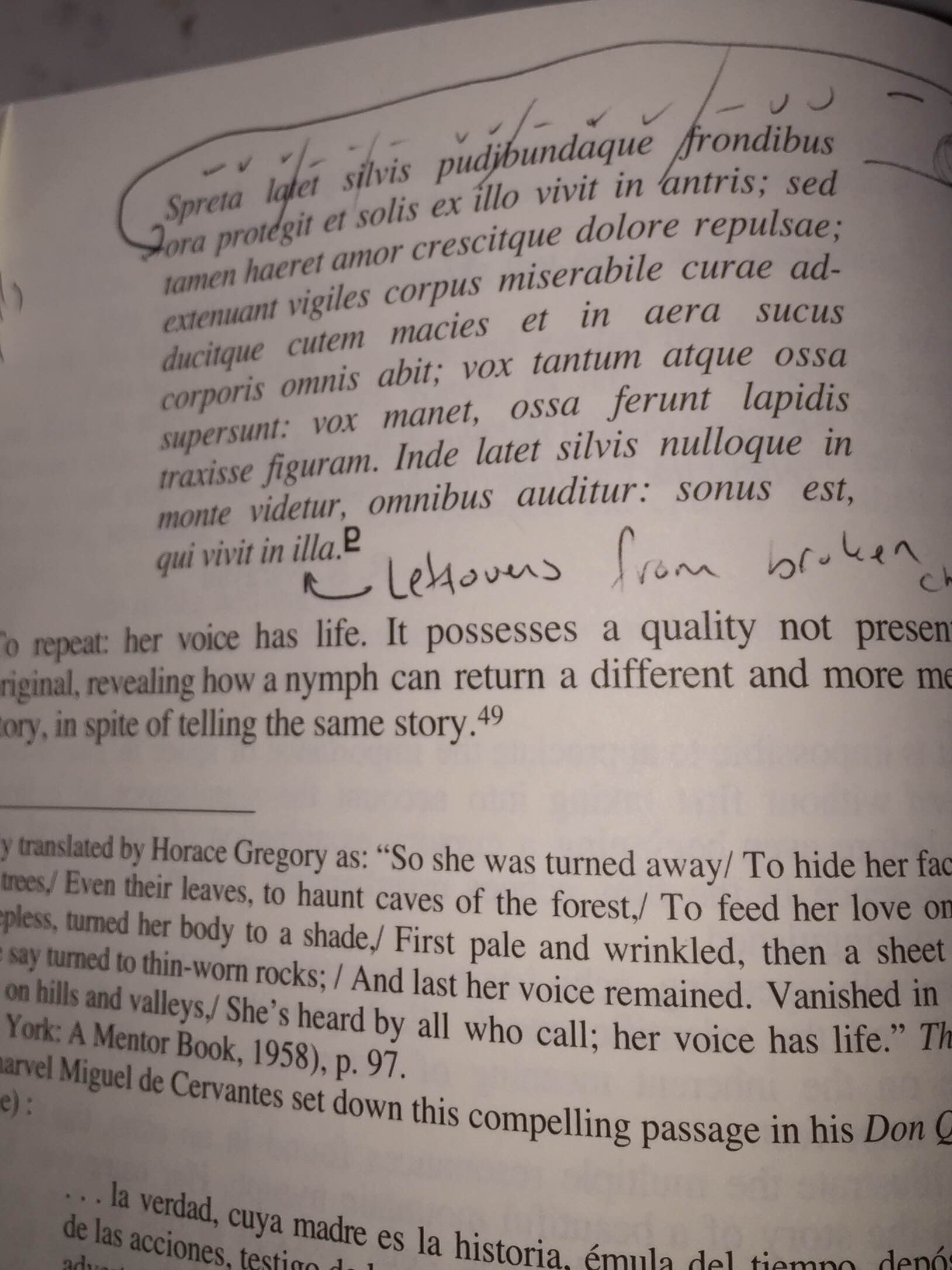

The next chapter begins a reflection on echoes and screams and their relationship to space. The commentary on this scene cites from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (my favorite Roman poem) the story of Narcissus and Echo.

The passage describes Echo who, having been destroyed disobeys her mortal bonds (like the “fitted” House?) and rebelliously responds and bounces about as a voice. But something struck my eye immediately about this passage: it’s as broken as Karen’s bookshelf. Someone monkeyed with the typographical conventions of Latin poetry. The immediacy of the “wrongness” jumped out at me so flagrantly that I had to check the poem’s meter immediately.

The Walls of Latin Verse

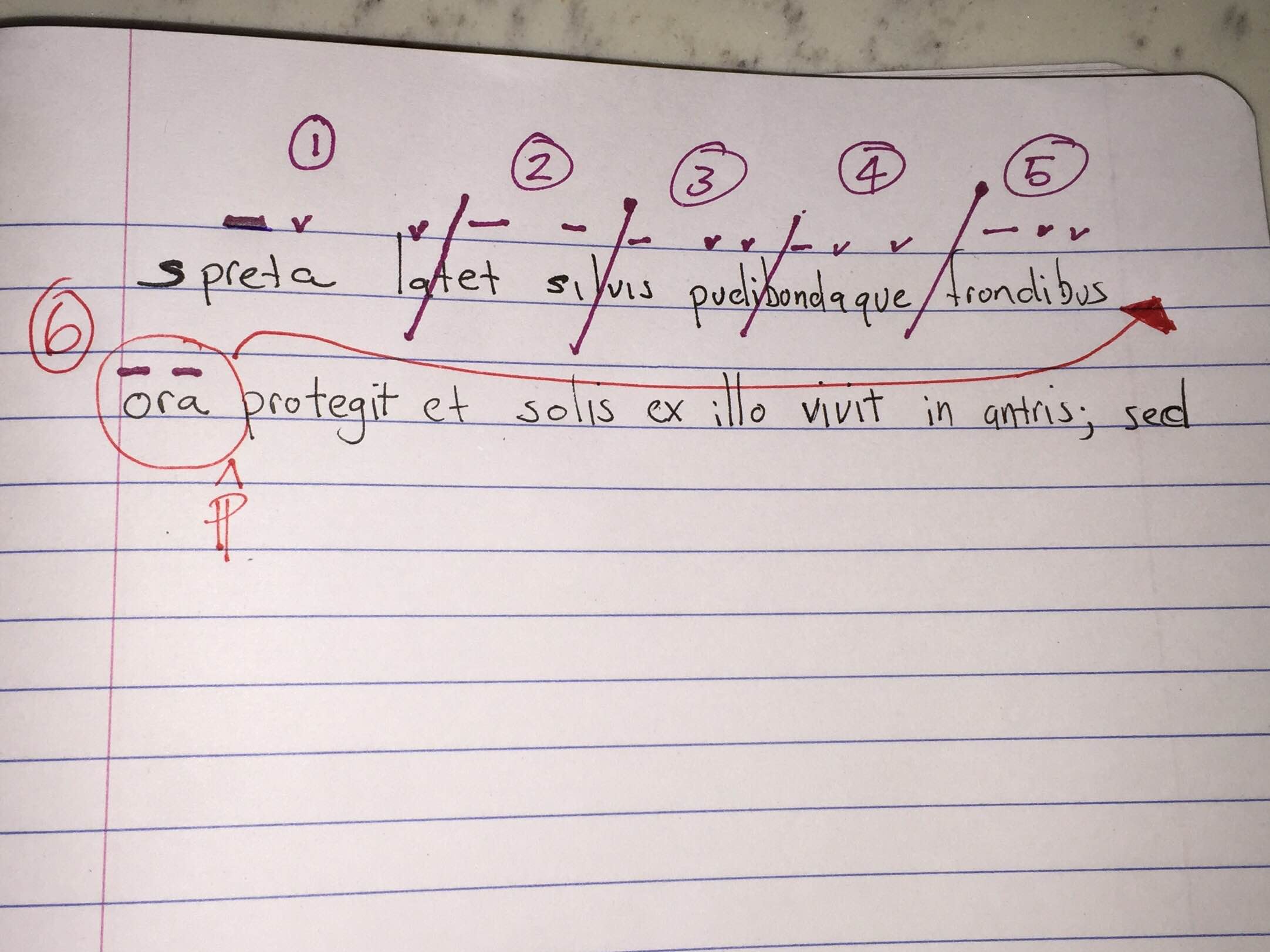

Ovid’s poetry is written in dactylic hexameter. It has rules namely that each line has six metrical “feet” and should end with the last foot being two long sounds. It has boundaries as sturdy and strong as walls. Consequently it has a certain visual structure, and tends to look roughly rectangular. Lines usually look justified, even, and don’t tend to have “ragged” final lines.

A meter-compatible typesetting should look like:

That is, “ora” (two long sounds) should have been at the end of the first line, but its bounding wall has been broken and it has fallen into the next line: just like the final book on Karen’s shelf which fell from its support onto the next lower support (the floor).

Conclusion

The book is full of other colorful references to semioticians, poets, critical theorists and is peppered with a heavy dose of smut. It mixes both high- and low-brow delights, and sports like Derrida’s jeux, in the interplay of textual contexts. For the classics students Danielewski found an exciting way to give us an extra dose of nagging error in the spatial dimension.

Footnotes

- How could it be? I recall those passages of Lovecraft which describe the unnatural horror that happens to us when we perceive geometry as being unreliable. I cite from The Call of Cthulu: “they all felt that it was a door because of the ornate lintel, threshold, and jambs around it, though they could not decide whether it lay flat like a trap-door or slantwise like an outside cellar-door. As Wilcox would have said, the geometry of the place was all wrong. One could not be sure that the sea and the…”

- Another “frame” in which House of Leaves nestles

- As a Danielewski-worthy footnote: she “fits” the boards perhaps in the same mode of the archaic use of the verb “fit” meaning “bested” or “conquered” as in “Joshua fit the battle of Jericho.”