Revisiting "Close Encounters of the Third Kind"

- 7 minutes read - 1447 words

- Format:

- Video on Demand

- Date Seen:

- 2022-10-21T19:00:00-05:00

- Venue:

- Prime Video

- Stars:

- ★★★

Nostalgia is a funny thing, and it gives our memories vivid colors that reality never had. I think Paul Simon, who has said many things well, may have said it best:

Kodachrome

They give us those nice bright colors

Give us the greens of summers

Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day, oh yeah

I got a Nikon camera

I love to take a photograph

So mama don’t take my Kodachrome away

A few lines later the narrator lets this fact seep through:

I know they’d never match my sweet imagination

And everything looks worse in black and white

During the final days of Lauren’s pregnancy, we were watching some “comfort movies,” and we decided to watch 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. While I’d seen it three or four times before, it was only in this viewing that a profound truth became glaringly obvious: Richard Dreyfus’ iconic everyman encountering the ineffable, Roy Neary, is terrible.

Turns out sending an emoji of a giant butte is alien for “You are a profound dick.”

In my Kodachrome® recollection, Neary has a Jamesian mystical experience that he can only render in sculpture (potato medium and purloined property), hunted by shadowy government officials and scientists he reaches Devil’s Tower, Wyoming, and is chosen by the extraterrestrials before he joins them to jaunt happily beyond Earth to frolic among the stars. It has the glitter and sheen of Spielberg of the early 80s: childlike wonder, lens flare, and the messy reality of family.

In black and white consideration though, the modern audience (myself included) asks: “Yeah, but what about his wife, his kids, the house he totaled?” The last they saw Dad he was in the midst of his Jamesian crisis and then he’s…gone.

As I asked myself this question, I had to ask, “why had I never thought to ask that before?” Only with some huge planetoids of socially-indoctrinated privilege could it be swallowed that Neary was a “hero” entitled to be a Terran ambassador of humankind’s best. But in the Kodachrome® memories of this film — he was. Privilege is a hell of a drug.

With the aid of critical theory (of the gender and economic kind), I’d like to unpack this movie a bit more.

Oh, and let’s just say what doesn’t need much saying: Teri Garr was criminally underused in this role.

Note: In this discussion, I’m discarding the alternate storyline that features a single mother (Melinda Dillion) whose son goes missing on the night of E.T. visits.

Consider the bones of Neary’s arc: An erstwhile family man alienates his

family, psychologically scars several of them in the process, and then takes

off on a grand adventure wherein consideration of them is entirely absent.

It’s the same outsize egomania and entitlement in Neary that we see in the

patrician protagonists of D.H. Lawrence or W. Somerset Maugham. Swap

“extraterrestrials” for “a dissolute can-can dancer named Gigi” and “outer

space” for “Place Pigalle, Paris,” and we’re basically watching and

apparently rooting for a man to abandon his family to follow his artistic

romantic path of Dionysian self-realization à la Maugham’s The Moon and

Sixpence. The abject cruelty (and/or blindness thanks to privilege) of Neary peaks in the following clip. Herein:

- Garr’s character, Ronnie, realizes:

- Her husband might actually be losing his mind

- Her marriage is in mortal peril

- Her children are vulnerable to a capricious man who may well turn violent

- That she may need to make a plan for life for herself and the children

sans Roy that involves:

- Flight to her mother/sister’s home

- Going back to work (an obligation she specifically told Roy she did not want to have to consider, given the kids)

- Their eldest son, Brad, played superbly by child actor Shawn Bishop, is realizing most of the same things as his mother Ronnie. He’s not so young that this will be the day “Daddy was funny,” this will be the exact moment that begins the first therapy session of many, many, many in his future.

After a rough night in the household, and after a night sleeping apart, Ronnie awakens to Roy tearing the house and yard (and neighbors’ yards) apart in an effort to build a more accurate representation of the butte in his mind.

At this point, Ronnie, sensibly, takes the kids away. While a cursory effort is made to contact Ronnie slightly later in the film, for all intents and purposes, Neary’s family has exited stage left.

Entitlement

In the end, I have to marvel at the power of the white Boomer male as made in God’s image. That an ostensible “hero” can inflict all this damage, but it needs to take a back seat to his Peter Pan-esque flights into his own dreams is a level of entitlement that absolutely boggles my mind.

Misogyny

As ever, doing any research on this topic on the internet is a dispiriting adventure. Much like Anna Gunn’s Skyler White to Brian Cranston’s Walter White in “Breaking Bad,” the unbounded support of (white) man-children behaving badly continues unabated. Recent threads on fora and social media assert that the problem here is that Ronnie isn’t being supportive enough.

Bullshit.

I read a lot of this in the “Breaking Bad” era that Skyler was probing and pushy and snooping too much while her husband was running…a murderous, illicit drug manufacture and intimidation empire. Walter is dangerous and becomes an unhinged monster. Skyler is trapped in the middle of what she doesn’t want to accept, what she can’t bear, and what she can’t seem to escape — huge echoes back to Ronnie Neary. Skyler’s meant to be an object of pathos; Gilligan gave Skyler her due in the final two seasons, but Spielberg never gives Ronnie a fair shake in this.

And also, the trope that Ronnie isn’t “supportive enough” is counterfactual to what Spielberg has shown us. Ronnie has stood by her man as he:

- Came home in the middle of the night and drove the entire family around the back roads of Indiana after waking them up at God-knows-what-hour

- Attended a civic venue and called the city leadership incompetent and left in a frothing huff

When standing by one’s man, always sport a swooping updo

Any partner who saw Roy’s level of change in a 72-hour period would be best serving their vows and civic obligations by getting the children somewhere safe and helping their partner find professional help.

Anyway, once the film takes Neary’s family out of the picture, we have a fairly fun road trip full of derring-do alongside Melinda Dillon (whom many of us primarily remember as “Mom from Christmas Story”) as Jillian. Whether that relationship is sexual or not is left ambiguous, but for a guy who had a family at Eggo o’clock a few mornings ago, he’s moving on quickly.

Huh, tastes of Lifebuoy

In any case, Roy and Jillian make their final flight to Devil’s Tower and arrive just in time for the big final set piece: the moment of contact.

Just..hats off to the camera. These colors are sublime.

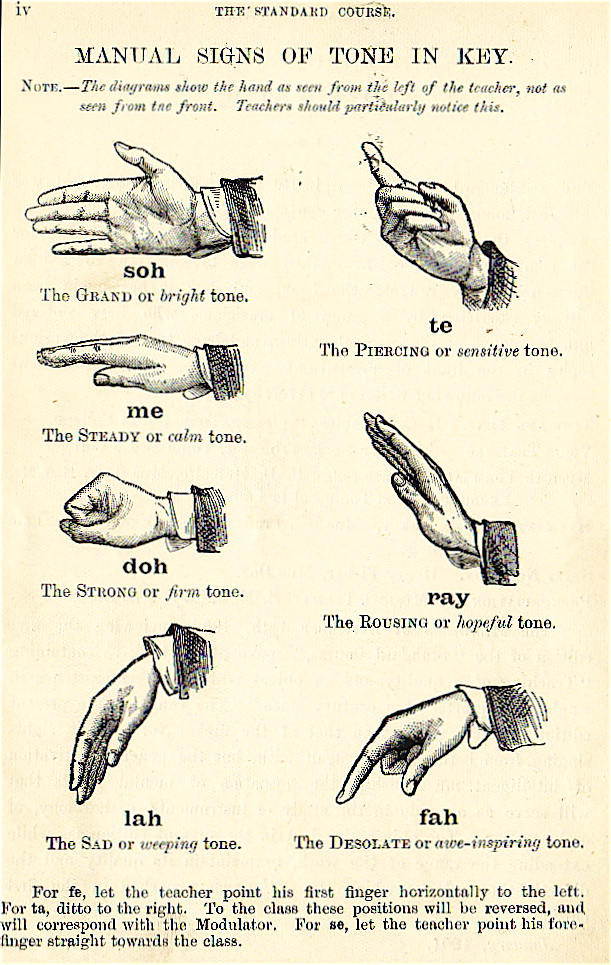

This is where the Kodachrome version matches on-screen as John Williams'

orchestral magic and Spielberg’s direction give us what we like to remember of

the movie: the wondrous conversation in Solresol (“The Universal Musical

Language”) augmented by the hand signals of the Kodály method

between ETs and government actors before a mother ship arrives and takes Roy on

a magic carpet ride cosmic exchange student program.

The Curwen hand vocabulary

and…

We’ve been trying to reach you about alien abduction insurance

It’s a breathtaking moment of first contact and establishes the now-stock science fiction trope that if a sci-fi team goes hunting for contact, they always need to ensure an audience stand-in linguist is in the away team for dramatic reveal and context-setting (“Arrival,” “Stargate,” “Annihilation,” et al.).

Conclusion

Watching it now, it’s an amazing waypoint on a career that opened with a bang on episodes of “Columbo,” rolled into “Jaws” and then came to dominate the early 80s so utterly. Additionally, it started that trademark vibe of wonder that Spielberg, even betimes as a parody unto itself (see: “Jurassic Park”), has so thoroughly tied his auteurship to. But this story simply does not work.

Perhaps the greatest wonder of this particular film is that a rank egotistical asshole and sociopath like Neary gets rated as being honorable enough to deserve the interstellar and spectacular happy ending he gets. While his wife, presumably, has him legally declared dead and bears the burden of supporting their kids.1

Footnotes

- Spielberg has said, to his credit, in interviews, that it was a mistake for Neary to abandon his family.