Dune

- 11 minutes read - 2305 words

- Format:

- Film

- Date Seen:

- 2021-10-23T14:40:18-04:00

- Venue:

- AMC Lincoln Center - Dolby

- Stars:

- ★★★½

Two of the most brooding, academic, philosophical, and beautiful sci-fi productions in recent memory were Arrival and Blade Runner: 2049 — both helmed by Denis Villeneuve. When I read that he was going to attempt to film the unfilmable1 Dune, I thought: “You know, he might have a shot at it.” I’m glad to say that he succeeded in the impossible: he has made / is making a Dune film worthy of the source material.2

Vision / Understanding the Source Material

Talking books with another human is a strange experience. If we strip away the fact that we’ve become comfortable with them, our questions to each other might look like:

- “Did the letter-shapes convince your brain to hallucinate in a way such that, when externally viewed as if you were a viewer on your hallucination, you thought this…?”

- “Did you hallucinate this impossible scenario similarly?”

Foremost, looking at the visuals, sets, and costumes, Villeneuve’s vision is within distances that feel small to my own hallucinations. Sure, I never imagined many of the details that he put on-screen, but, in substance, my brain recognizes his presented vision came from a hallucination similar to mine. True fans knew where to expect the gasp moments. Seeing those moments and then hearing the gasps of fellow true believers and their less-rabid friends confirmed that Villeneuve was one of us and was succeeding in weaving a spectacle that united all our individual hallucinations into his.

What a costume on the Lady Jessica

In many places, Villeneuve opted for practical effects or shoots on location. As such the world looks lived-in, and real.

A perfect location shot; beautiful costumes

Pacing / Talking to Myself

Villeneuve lets the images breathe

One of the real challenges of in the book of Dune is that as Paul’s mind is warped by his spice overdoses, he talks to himself. Well, that makes for boring in a medium whose primary decree is “show don’t tell.” I can remember whole scenes (emphasis on the plural, there) of Kyle MacLachlan whispering to himself in the Lynch version.

Instead of transplanting the talking bits from Herbert’s source and repeating them as apostrophe, Villeneuve demands his Paul show something in his expression, in his posture. Fortunately Timothée Chalamet is up to this requirement. Villeneuve intercuts visions occasionally and adds in mysterious audio cues, but what they mean, why, and where they’re coming from are left mysterious. All we, and Paul, are given is some insight and an aching curiosity about why it came. It cuts down scene runtime and builds mystery. That Villeneuve threads that balance is a tribute to his decision-making.

In general, though, his choice to be comfortable with the mysteries of the Dune-universe is just a specific case of a consistent directorial choice. Villeneuve has enough French film (he’s French-Canadian) history in his DNA that he can simply let beautiful images be; even strange, wild, sci-fi images. He lets beautiful, strange images just sit on screen. Much as he did in BR: 2049

Office space in BR: 2049

or the alien sequences in Arrival:

Heptapods speak in time-bending circle

In Villeneuve, fantastically composed scenes are given time on screen to breathe.

For example:

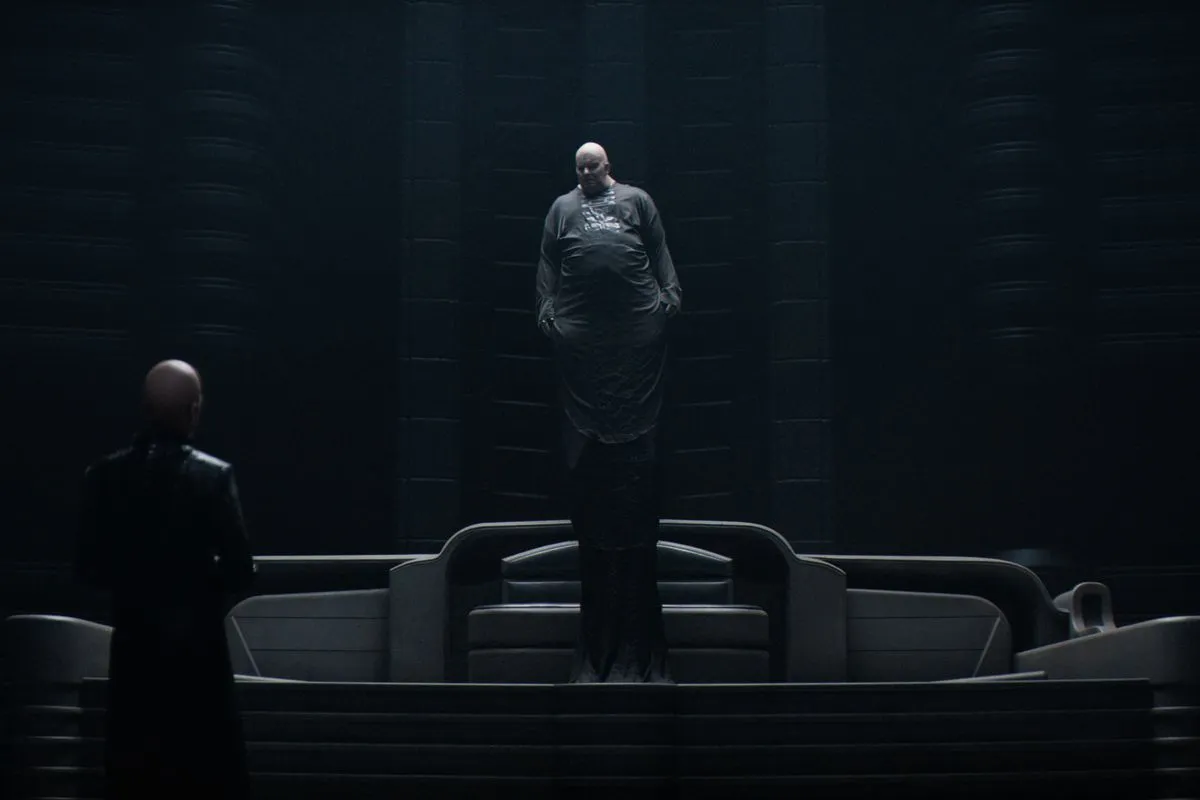

Baron, victorious

An invading, floating, and corpulent baron enters, after his blitzkrieg, in silhouette. His troops march. He floats. He’s in no hurry. He doesn’t need to hurry to gloat, he has utterly won.

Later, we see Oscar Isaac composed like a Caravaggio as a nude prisoner before the Baron.

Caravaggio-esque

Later yet, we see sunlight play in the redoubt where Idaho will show his devotion and lethal skill.

Mortiturus vos necat

Casting

The casting for this film was stellar throughout. While I praised Momoa (“Idaho”), I’d also like to call out Timothée Chalamet and Rebecca Ferguson.

Every time I see Chalamet off-screen, he strikes me as being an affable stoner or skateboarder who’s inclined to knock-off a sideview mirror on your car on accident while doing some trick between grape Slush Puppy sips in the parking lot of a 7-11. But, I cannot deny, on-screen, he’s got presence and control. He was stellar in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, and here as well.

For her part, Ferguson does a wonderful job bringing a much richer range of emotions to Lady Jessica. While I still love Francesca Annis’ portrayal in the Lynch version, Ferguson tones down the queenly imperiousness and amps up the resourcefulness, latent violence, intelligence, and sorrow of Jessica and brings her closer to my imagining of her character based on the book.

Novel Foci

The movie starts in a novel way. While Lynch’s version starts with Princess Irulan, daughter to the Emperor, narrating the beginning of the events of Dune from an Imperial perspective, Villeneuve starts by letting an oppressed native, suffering under colonialist exploitation, tell where her history is. It puts the thread around resource extraction, climate change, opportunism between church and empire, and oppression that’s front-and-center in the book in a marquee position.

The movie also makes a novel non-focus of the trip from the Atriedes homeworld of Caladan to Arrakis. Knowing that we know what fold-space or faster-than-light travel is in the 21st century, Villeneuve skips the presentation and leaves it at: The Guild has a monopoly, they use spice to make it happen, and it happened here. Now, desert.

Sets and Costume

Just to repeat, the costumes are stellar. On their arrival, Jessica’s bronze gown with a head mask made of chains and a train whipping in the wind tells us so much about her strength, her obligation, and her royalty. Throughout the runtime the costumes are phenomenal.

Similarly, the sets are fantastical with early-60’s sci-fi grooviness embedded in the typefaces, wall art, and cues from Middle Eastern life.

Sandworm relief-art wall

SPOILER WARNING After this point, some slight hints may be dropped that may spoil parts of the film or characters’ fates.

Updating the Source Material

If carefully recreating a common thread to all the mind-hallucinations that the fans had of the book was table stakes, Villeneuve shows himself to be gifted in that he makes a few edits to some of the characters’ arcs that, I’d contend, improve the story.

“Duncan Idaho” played by Jason Momoa

‘Duncan Idaho’ played by Jason Momoa

Much as Boba Fett has always held an outsize fascination for some Empire Strikes Back fans, Idaho, played perfectly by the magnetic, affable, and joyous Momoa, has always had a cult following in the Dune fandom. In the book, well, he dies early. Idaho is overwhelmed by the imperial thumb-on-the-scale assault wave of Sardukar (elite troops) during the blitzkrieg. Villeneuve must have sensed that this was an error and gives Idaho more stage time and a longer life so that we can see why Paul might be so deeply loyal to this man. In the books, deep loyalty to Idaho becomes a major plot point in the second books onward.

“Liet Kynes” played by Sharon Duncan-Brewster

‘Liet Kynes’ played by Sharon Duncan-Brewster

Similarly to Idaho, the planetologist Kynes (a gender-swap from the book) gets a swift and inglorious death in the book. He’s stripped of his stillsuit and tossed into his desert. Dehydrated and near death, he finds an instant-quicksand patch of sand and is swallowed by the planet. The end. Villeneuve extends this Kynes’ arc by letting her ferocity, capability, and resourcefulness shine through until she’s murdered on her feet, like a warrior, like an inhabitant of both the Fremen and Imperial worlds.

“Beast Rabban” played by Dave Bautista

‘Beast Rabban’ played by Dave Bautista

Played for grotesque camp in Lynch’s Dune, Villeneuve’s interpretation of the Baron’s lackey and unwitting dupe in a secret plan held by the Baron (Stellan Skarsgård) is done wonderfully with a lot of subtlety by Dave Bautista. Bautista, fresh from multiple outings as the affectless Drax the Destroyer in the Marvel universe, has clearly given a lot of time to thinking about “What do dim-witted muscle-men actually think?”

In a pivotal scene, Rabban encounters plans and calumnies that are beyond his grasp. He doesn’t understand why Arrakis, the planet Dune, is being taken away from them after they exploited and oppressed so well for so many years. What’s a character written as an emotional, violent, strong, oaf to do? Bautista does the most reasonable thing possible: he asks someone he regards as cunning and perfidious to explain it. He’s not smart, and he’s smart enough to know that; but, in the way that he knows he is stronger than most and he is scary for it, he also knows others are smarter than most and scary for it. He asks his uncle, the Baron, to explain what happened. It’s a moment where Villeneuve helps a character become more full and catches the audience up on a subtle piece of machination.

It’s insightful decisions like these that repeatedly confirm Villeneuve’s unique talent for guiding this effort.

Kwisatz Haderach Description

Determining whether Paul is animal, human, or possibly something else

One of the key plot points is that Paul Atriedes might be the achieved goal of a centuries-long eugenics program; he might be a being known as the Kwisatz Haderach. While the book and Lynch both take this term to mean a spiritual guru, Villeneuve guides a different interpretation from the mouth of the Revered Mother Mohaim (played by Charlotte Rampling). Her guidance is that this being’s brain and mind will be different. Because his physical brain will be “improved,” his mind will be able to consider outside the bounds of the Kantian conditions of experience: space and time. That is, the two fundamental axes which bind perception will not bind his thinking.

This has wonderful echoes in the universe: guild navigators travel space by “folding” it, Paul is awakening to the ability to see the future (or, is that, not be confused into seeing a difference between “now’ and “then?). This is a really exciting interpretation of this mythical title and keeps Paul and his significance in a more mechanistic version of reality.

Additionally, in describing the KH, the Revered Mother hints that Paul might very well fall short of the target. But she also admits he’s close, and might manage to save himself / be of some use if the right circumstances happen about him. But the circumstance is left unnamed. We, as an audience, see the thing she feared as dramatic irony: massive, repeated, spice saturation is the condition that might unlock KH channels in Paul’s mind. Thus, we, as the audience, see Paul zoning out in spice reveries, gaining knowledge, falling incapacitated…but we understand why and we also understand that the long-term effects might be to unlock an awesome and terrible, godlike even, power latent within him.

Conclusion

All told, I thought this was a brilliant interpretation that was cohesive and honored the book. Bravo.

Tangents

Background on the agony and ecstasy of previous attempts to film Dune

History of (Mostly-Failed) Dune Film Adaptations

When I first read the book, in the early-90’s, I soaked it up and then went to see the glorious folly that was David Lynch’s film adaptation. With the vast budgets of the de Laurentiis production house, the toast of early 80’s European cinema as cast, stunning sets, and fully-realized costume, it was an epic disaster — a beautiful catastrophe. Apparently during the initial release, a pamphlet was given to viewers that outlined some vocabulary and key players. That is a death-knell 💀. The story seemed too big between the political players and the mental transformation of the protagonist, Paul Atriedes. Additionally the film suffered for Lynch being Lynch:

-

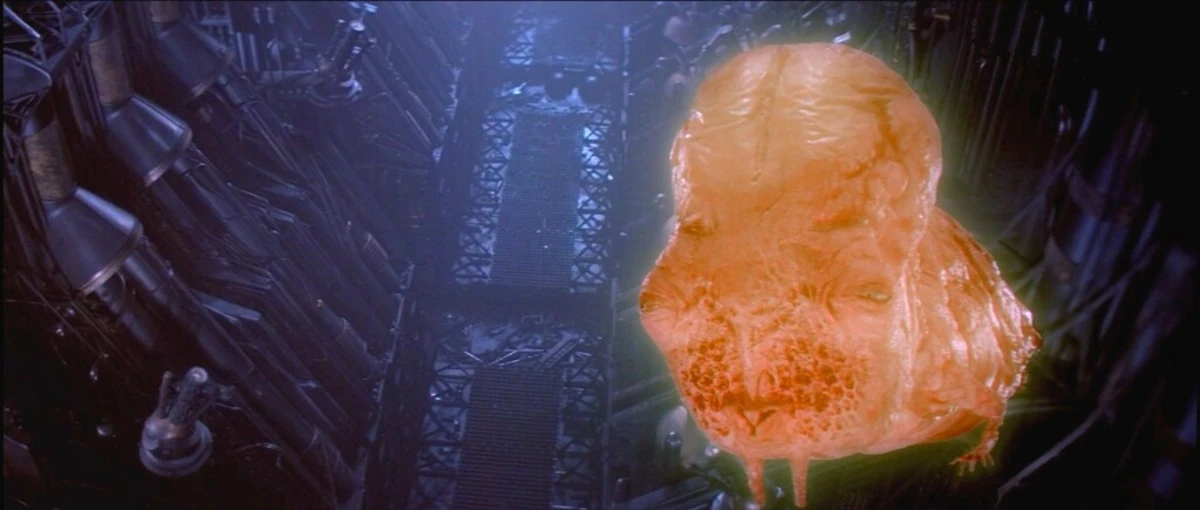

Overlong scenes depicting floating space fetuses with mouth vaginas folding space. No, really:

Once you see…

-

Over-literal lifting of dialogue from the book

-

Unrestrained direction of actors, chiefly Kenneth McMillan’s “Baron Harokonnen” who floats into the camp stratosphere with his grotesquerie

Lynch unbound

-

Inexplicable additions like:

- Harkonnen citizens have pull-tab vales in their hearts for easy killing

- A cat-rat hybrid

- A magic space sidearm powered by sound (what?!)

In the 2000, the Sci-Fi network made a miniseries adaptation. While these had some improvements, they missed other marks. Taking advantage of decreasing costs of green-screen/CGI and Eastern European filming, Sci-Fi stretched their budget, and proved that a longer runtime would provide the ability to stake out the political factions properly. Nevertheless, these movies look less substantial than Lynch’s outing by preferring green screen/CGI to (Lynch staple) practical effects.

Additionally, the inexplicably wooden portrayal by William Hurt as Paul’s doomed father, Leto, ruined the opening act (what in hell were they going for?). Additionally, it’s amazing that in a universe made up of far-flung humanity surviving a population apocalypse, everyone is Caucasian. The series was also made slightly before the “peak TV” phenomenon where we realized that some of the biggest “movie” talents shine better on TV than in film: in this case, the acting talent is clearly second-tier to the work in the Lynch version.

Footnotes

- I had largely considered Dune unfilmable. It features internecine ducal political dynamics on the scale of Game of Thrones. Its realization calls for practical effects, casts of hundreds, custom sets, and top-flight costumes. And when the plot isn’t space-Borgia Italy, it’s a man experiencing his consciousness rewiring itself from the inside— not the stuff ideal for a visual medium. All told, these constraints stand make production expensive and yet shortchanging on any of them would lead to another failure to film the story. For more on the failures, see the Tangents section.

- Full disclosure: I am a huge Dune universe fan. I have read the first book somewhere in the neighborhood of twenty times and the entire original series at least twice. I have whole passages of dialogue memorized for no reason other than sheer exposure. I am squarely in the target demographic.