Village of the Damned (1960)

- 7 minutes read - 1480 words

- Format:

- Film

- Date Seen:

- 2022-09-11T13:59:49-04:00

- Venue:

- HBO Max

- Stars:

- ★★★★½

This might well be a perfect scifi-horror film. Drawn from the book The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham (author of Chocky, progenitor of biophilic horror), an entire town passes out. An outsider comes to delimit the zone in which all consciousness fades (à la the Southern Reach) when suddenly the blackout ends, with seemingly no ill effect. Over the coming days, fertile women find themselves inexplicably pregnant. Months later, simultaneously they beget “arresting-eyed,” blonde children of exceptional intellect and rapid maturation.

While the presentation in this film is superficial (no women have speaking roles or volition; no women talk to each other about the fact that they’re pregnant, etc.) due to the constraints of its time, the thought-provoking barbs laid by Wyndham give flashes of insight, complexity, and terror. The movie holds up for its time and for of its era, but it also suggests deep questions about society, arms races, and the need for idiotic savage populism within the general population. It’s an iconic work with deep and wide impact beyond its reference value in Simpsons episodes.

Their writers never miss a good pop culture icon

I’d like to pick up a few themes that appear in the film, rather than comment on the acting and production. Like most sci-fi, it’s really about the ideas and less about the actors.

The Black-Out

When I’d read the synopsis of the film, I had always taken the “black out” to be something about an electrical grid. But it isn’t. It is, rather, a great “blacking out,” a great and sudden sleep. Because of this, the movie opens, inexplicably with the great sleep and we’re treated to scenes of bucolic English life arrested: cows lie on their sides, irons are left burning, basins are left filling, buses go off the road.

Eerie

Arial shots of the village prove exceedingly eerie as the normal movement of life is simply absent. It’s a fore-runner of the profound eerieness of, say, “28 Days Later” or “Vanilla Sky” where Cillian Murphy wanders a vacant Westminster or Times Square.

The green hospital scrubs stand out against London

An empty Times Square; apparently it cost a ton to shoot this

Both of these latter movies clearly serve as homage to Village. Additionally, this story happens barely a decade after the end of WWII. Telephone service is still brokered through a shared trunk where the wealthy (like our scientist/gentleman protagonist Gordon and his wife Anthea) dial the village operator-cum-busybody to be linked to the outside world and the local constable is powered by muscle and his Doctor Marten’s clad feet on bicycle.

Begone blackguards and slatterns, my lady-wife and I demand use of this key light!

The Pregnancies

While 1960s British moral code laws for film prevent the outright saying of what the science fiction author Wyndham clearly meant to say, the sudden pregnancies unlock a Pandora’s Box of social custom/honor code/honor killing/cuckold anxiety within the village.

If this film were re-made today, these themes could really be explored. As was, all these topics had to be elliptically referred to in the mode of their time with the euphemism and ellipses of their time. When you know to read between the lines, the dialogue heightens the tension.

For example, a young girl sees a doctor and learns she’s pregnant. Now the doctor has clearly encountered girls “who got in trouble” or “who needed their boyfriend to have a word with the doctor” before. But the poor child is weeping because she’s actually a virgin. Even then, she might not even have had the sex education to know that it’s actually impossible for her to have become pregnant. The taboos and morality hinder the attempts to actually understand what happened.

Another example, a middle-aged woman, whose husband has been at sea, finds herself fallen pregnant. We’re given moments of tension where we have to decide what he believes about his wife; and we’re left with a tense moments where we are left hanging whether he’s going to beat her (or worse). He storms out off to the pub instead where he’s forced to eye every other man in the room as a suspect.

Against both of these violations of patriarchal ownership of women, we can see ancient rules of primal law butting against modernity. Rules about honor killing of “ruined” daughters, honor killing of unfaithful wives rear up from our collective unconscious history into the very moment and we get to pat ourselves on the back with “we’re not so barbaric as all that.”

But Wyndham doesn’t give an easy out on this, instead it’s the barbarians whose “stone age” custom are actually protecting humanity.

The Necessity of Primitivism

Wyndham inverts our sense of smugness delightfully as we discover that several other villages were similarly “paused” and reawakened to inexplicable pregnancies. However, in those “primitive” parts of the world, the lex honoris is still in force, and odd-looking, blonde children and/or their mothers were murdered on sight.1

The only villages where the children survived were Midwich and one in the USSR. The only “non-primitive” cultures that were “paused.”

The Pursuit of Knowledge

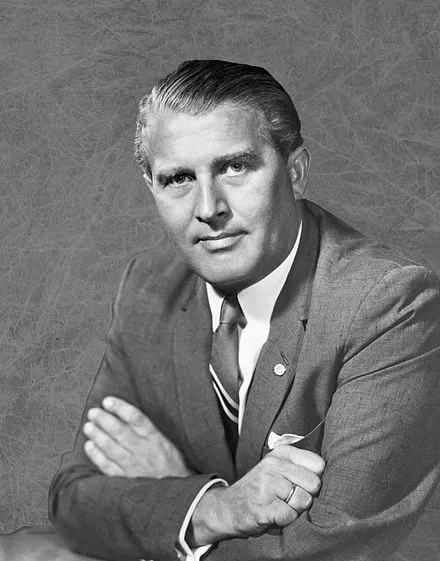

The children, with their powerful intellect and sophistication, also act as a symbol for the Cold War (after the “primitive” societies are “liberated” from the risk of trying to use these demigods). They represent, to me, atomic knowledge. The West versus the USSR see these children as a force which can help them leapfrog the other, but fail to calculate the existential risk they pose to all humanity. In a 1960 release, this is poetic and cutting. It might even have a less encoded reference, referring to Operation Paperclip wherein the US extracted Nazi scientists and relocated them to the US to build our rocketry/outer space programs.

Wernher von Braun; driving force behind two rocketry programs

The Necessity of Primitivism (Again)

As a Good Liberal™, it was a novel feeling to watch a pub of alien-cuckolded2 agricultural-class pub-goers get riled up and take up pitchforks and torches to hunt down the invaders-camouflaged-as-children “intellectuals” in a “raid on Dr. Frankenstein’s castle” moment. Wyndham has us see the utility and benefit of populism and mob ire. It’s humanity’s last chance at stopping these “children.” Is our old, purportedly barbaric wiring, without use? Perhaps our populations are benefitted by having a barely-contained mob-violence instinct? Anyone whose seen their dog lash out and pack up against infirm dogs (or people) knows the embarrassment…and the wariness the dog might know something that taboo or decency refuse to let us let ourselves discuss.

Howlers

As any movie of its era, there are some real points of eye-roll for the modern viewer.

- There’s an obligatory slap a woman out of hysteria scene.

- It’s also inconceivable that the semi-shunned pregnant women wouldn’t…talk…to…each…other? Instead they all get (hah!) x-rayed to verify pregnancy, are humiliated, and never talk to each other that we see.

- It’s semi-inconceivable that none of the cuckolded men wouldn’t talk to each other. Manly ego being what it is, there would have been some suspicious tension, but after a half-dozen freaky-looking kids turned up, I think the old anxiety could be reasonably suspended.

- Rank classism: the rustic townies are lorded over by the military, the wealthy scientist protagonist who lives at the village’s manor, and his career military brother-in-law. They know when to bow and scrape and do.

Filming Technique

Spoiler

The final scene where our Hero enters the “childrens’” school with a time-bomb and must fend off their psychic attack is superb and recalls the clock-driven tension from Hitchcock’s “Sabotage (1936).” Director Wolf Rilla overlays an image of a brick wall (of which Our Hero must think in order to keep his mind closed) on top of an image of a ticking time-bomb. As the wall shows wear and crumbling we understand this to be the battle between the alien and the hero. It’s only with seconds left that the wall falls. This was just a cool sequence.

Conclusion

For a shockingly small 70 minutes, this movie packs one hell of a punch in terms of performances, ideas, jarring images, and impact. It’s a strong recommendation.

Bonus

Both the Mrs. and I couldn’t get over what a babe Barbara Shelley was. Sometime later she became a fixture in the Hammer pictures horror films:

Barbara Shelley

Footnotes

- A product of its time, in this production, Africa, non-English Empire Asia, and Australia are all “primitive” and so are all inhabitants (save English colonists). Wyndham was a product of and the production is a celebrant of Imperial England (moments after its zenith).

- The title of Midwich Cuckoos becomes clear. The cuckoo throws eggs out of a creator bird’s nest so that it can deposit its own egg into the nest and have the owner incubate the egg on the cuckoos behalf — this lets the cuckoo get back to the all-critical game of producing more eggs.