"Christopher Robin"

- 5 minutes read - 986 words

- Format:

- Film

- Date Seen:

- 2018-09-15

- Venue:

- Regal Battery Park Stadium 11

- Stars:

- ★★

Saturday we took a bike ride down the Hudson River to Battery Park City where we saw “Christopher Robin.” It continues this strange trend of Disney taking one of their properties, turning 17.5° off from it and then writing some meta-script about the story e.g. “Saving Mr. Banks”.

I had had high hopes based on the reviews, especially those that suggested that there was something for the grown-ups here too (like most Pixar movies deliver). I would disagree with this assessment. It was enjoyable enough, but I kept seeing the glimmer of something so much more amazing again and again and was disappointed to not see that movie.

To my mind, it failed because of its incautious handling of the Hundred Acre Wood and because its characterization was flat to the point of insulting.

The Imaginary World

The first failure, in my viewing, was how they dealt with the question of a fantasy world. Whenever such a world is posited, the story has to work out what the “real world’s” relationship is to the fantasy world. Is it all in his / her head e.g. “The Science of Sleep” ; Is it real, but only some can see it (and why) e.g. “Harry Potter;” etc. “Christopher Robin” plays by one set of rules and then shifts to another in a way that’s both baffling and disappointing.

The movie starts with us drawn into an imaginary tableau on a beautiful hill in Sussex. We see the familiar toys having a tender farewell for Robin who is soon leaving for boarding school. It’s right in the sentimental spot of “The Velveteen Rabbit” and plays beautifully. We’re in the honeyed realm of make-believe childhood. The world is in his head.

However, when the characters return to Robin’s life, they appear to be real. Neighbors hear Pooh’s muffled complaints, train riders do too, eventually Robin’s wife and child do. The fantasy world is real.

At this point, we have to ask ourselves “Just what the heck is happening here?” If the imaginary world is not symbolic, the characters are not vivid reverie, and we’re not in a fantasy world where imagination and “real world” commingle e.g. “Harry Potter.”

And this is a real shame, I kept feeling like a careful writer or director could have made it “It’s in his head” and carefully constrained who “in the real world” saw them. Working out a “rulebook” on how and when your fantasies come to save you could have been really special and tender — although in such a case we would expect all adults to have a fantasy world personal to them versus participating in Robin’s particular fantasy world.

The Importance of Fantasy

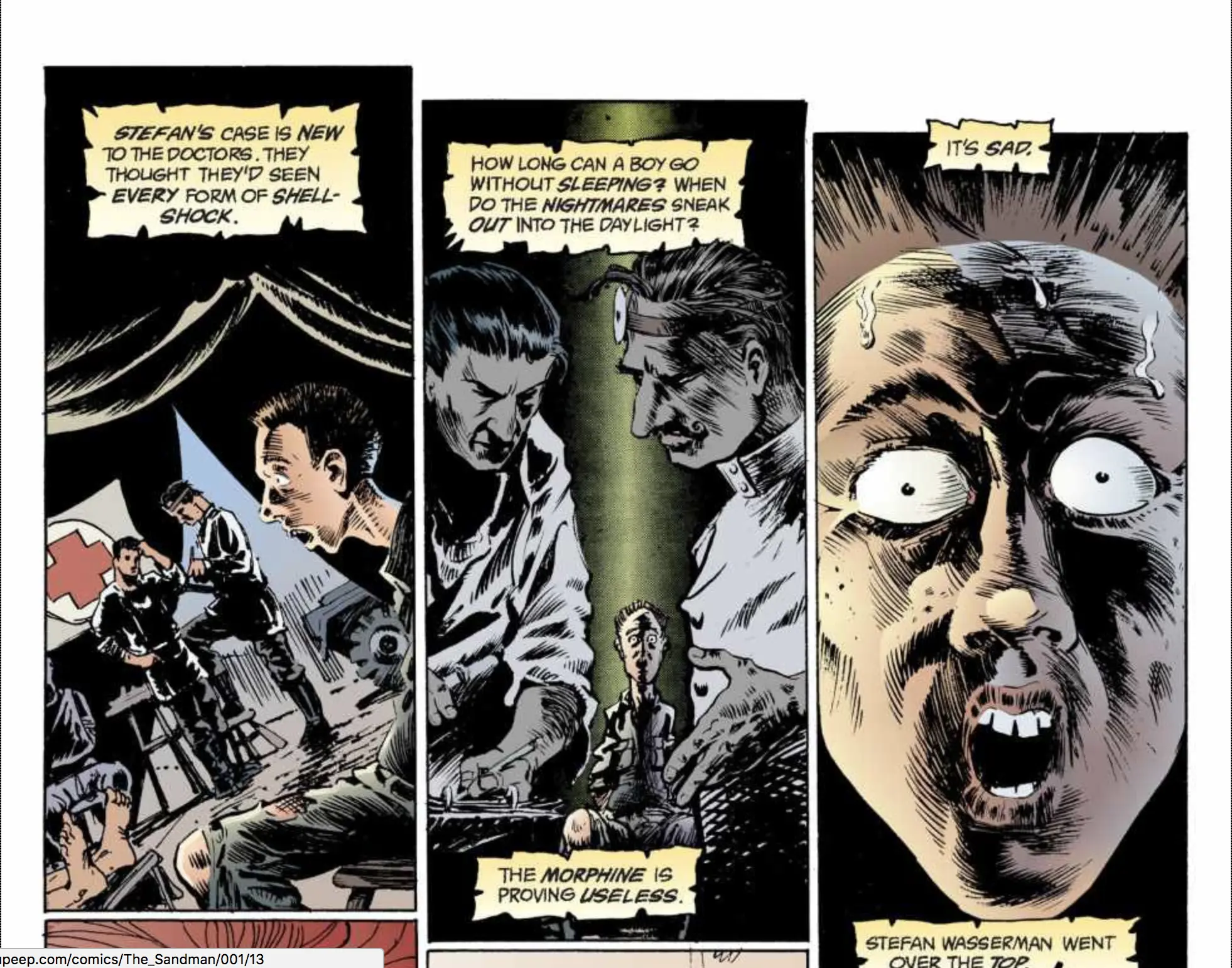

I believe fantasy has an important role to play in the psychology of the adult. Those with a vivid fantasy world can offload stress, can be better present with children and friends, etc. In Neil Gaiman’s “Sandman” we’re shown how dreaming helps humans stay, quite literally, alive.

Fantasy is salubrious

The majority of “Christopher Robin” takes place after the eponymous charachter returns from WWII. Returning to England with PTSD, etc., seeing the Pooh-corner characters emerge to help him out of his shell shock, to reconnect with his wife, and the daughter who was born while he was deployed would have been amazing, tender, and fantastic. What if, by teaching her father to animate those stories again, daughter were to help him back into the world? It’s this missed opportunity that could have made this a profound story, instead of a merely entertaining one.

Characterization

But perhaps deeply-engaging plot arcs lamented above were destinated to be impossible because the characterization is so flat and over-simplified. While the actors do the best with the material they’re given, they never escape being one-note or caricatures.

Despite seeing that Robin had an amazing imaginary life, showed valor on the field of war, and was adorably bumbling in meeting his wife, Evelyn (played by Haley Atwell, the queen of war-era Britsh woman roles), by the time we catch up with him in the 1950’s he’s devolved to a Walter Mitty-esque, middle-management drone. His boss (a waste of Mark Gattis) is a simple, sneering, entitled one-percenter who shriks work to better his, hold your surprise, golf game. “Christopher Robin” has become “Dagwood Bumstead” and falls victim to rehashing many of the 50’s-era comedic tropes of the bourgeois be-saddled bumbler.

Evelyn and Madline, discussing Chrisopher Robin

The real crime is Hayley Atwell who is reduced to a lot of screen-edge sighing and father-excusing whispers to their daughter. While the exposition includes her bravely bearing a stiff upper lip while pregnant through the horror of the blitz (where was her fantasy out?), once back in peace-time she has no real part but to advance Robin’s narrative. Apparently cut from the film were aspects of how her drafting helped rebuild London. While we see her working at a drafting desk we never see anything else of this: y’know, her hopes, life, and dreams.

Over and above this, I find it vaguely insulting that instead of having a relationship with her Robin (reverts? summons?) his fantasies into reality. That’s just kinda cruel. The pain she suffers in the wake of Robin’s detachment, PTSD, checked-out parenting, and checked-out marriage cease mattering once she meets the (holy cow!) stuffed animals come to life.

As a counterpoint, what’s interesting is that “Mary Poppins” hits most of the same notes, but nevertheless builds characters with some degree of richness. Oddly, “Mary Poppins” does a much better job at passing the Bechdel Test…despite being decades and several hashtags older.

The Characters at Pooh Corner

On the up side, the characters of the Hundred Acre Wood are beautifully animated and voiced. But you knew it would be impossible to go wrong there.

Conclusion

For a show that’s so rich in setup and technical execution, it wound up being a Film of Very Little Presence.