I’m an avid reader. I like to post book reviews here. I also add extractions of highlights and favorite quotes in the form of JSON payloads created with a tool I wrote called AmaJSON.

Rereading "Watchmen" 26 Years Later

Rating: 5.0 / 5.0

Rating: 5.0 / 5.0

Note: This take is entirely based on the original comic, with some light reference to the theatrical film in preparation to watch the HBO series. I am writing ignorance of the latter.

A lot of the best parts of college come come fast and furious in those early months after you move in: local food dives, parties, outdoor hangouts, new friends, new habits, new hobbies, strange professors, strange friends, new books, new music, and new ideas.

Around October Fall 1995, Watchmen came my way. After having been a fan of Vertigo’s The Sandman series in high school, I knew that there were serious comics about adult (not per se sexual, although…) ideas out there, but I was unaware of just how serious Watchmen was.

Throughout the years, many of Watchmen’s ideas came true:

- venal narcissism in the Oval Office (beyond a Nixonian level)

- massive information culling, prioritizing, interpreting, and stock market-gaming intelligences

- morally rigid puritans exerting their will through murder of those who would lead them astray

- wűnderkind billionaires giving natural selection a helping hand by setting the species’ targets among the stars

Additionally, Watchmen itself went through some strange intellectual property waters:

- re-issues

- an original-intent-obscuring movie release that didn’t quite hit the mark

- a direct-sequel series on HBO that was widely-acclaimed and has proven to be a forum wherein the formidable talent of Regina King was finally recognized

With the desire to watch and grab some of the background context of HBO’s “Watchmen,” I decided to give the paperback a re-read and see how it’s held up. Spoilers can be assumed for anyone reading onward.

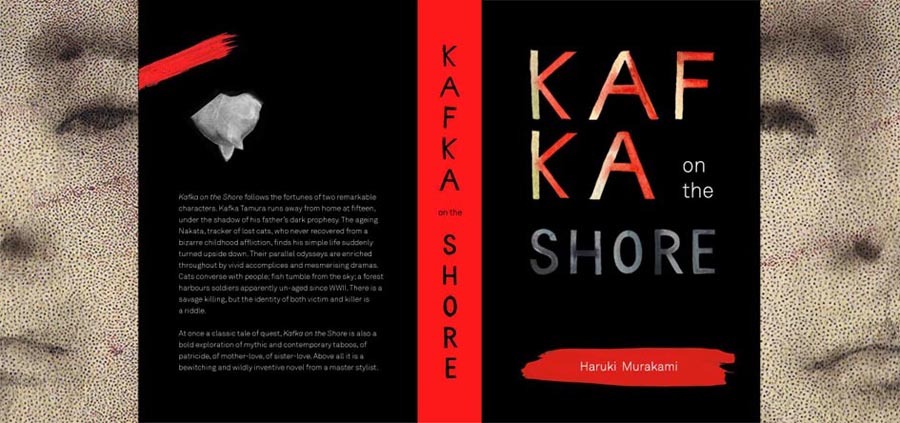

Kafka on the Shore

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

I read this book a while back, but I never managed to post about it.

I liked it a lot. Similar to 1Q84, there was world-bending and a magical substructure to daily life, but I enjoyed the characters’ journeys and the beautiful descriptions of rural Japan. If ever I make it there, I truly hope to be able experience the fields and forests of the more-remote islands.

Having looked through the notes I marked, I’m really in awe of the quality sentence construction expressed in the annotated lines. In particular, I’m really picking up on the theme of that sometimes things bear a name that doesn’t change, but they are, in definite ways, something entirely than they were previously. Take a look at Murakami’s thoughts, recalling Heraclitus, about things being new, all the time, in the illusion of the “present moment.”

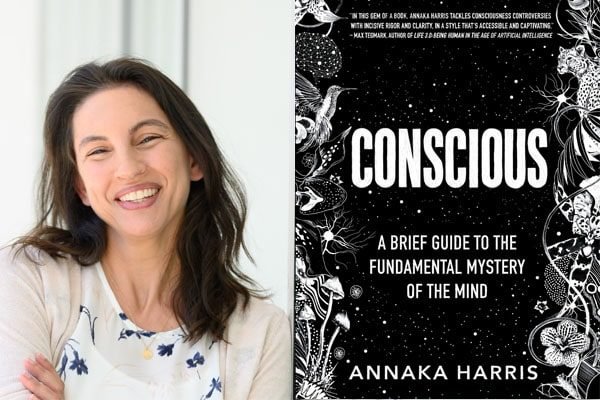

Conscious

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

Review

Having heard a few interviews with her, I’ve enjoyed Ms. Harris’ perspectives on consciousness. I became familiar with this work via Sam Harris’ podcast where the Harrises facilitated a discussion with Donald Hoffman.

Both Conscious and Hoffman’s The Case Against Reality suffer a primary problem: what they propose is extremely jarring to our daily experience. They bear the burden of presenting some evidence that reality is not what you think of in daily awareness. Their method is to jar the reader one millimeter so that they can open them to being willing to move 1 kilometer. As a result, the books recount anecdotes and experiments designed to “freak the squares” as the hippies might have said.

Vacationland

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

John Hodgman’s Vacationland is a very funny and very touching book.

The Hodgman character (of dubious relation to the actual person, John Hodgman) is a delightful know-it-all. This persona served as the basis of his “PC” character in the Apple computer ads of the early aughts and was also the know-it-all voice of his book “The Areas of My Expertise.”

So to have this persona describe the problems and terrain of the Trump era and its attendant commitment to non-reality is bound to produce some comedic sparks. How does this Yale-educated, Park Slope-dwelling early-Gen-Xer, whom Fortune has blessed, face the prospect of aging, the maturation of children, and meeting his musical heroes of his youth? How does he reckon with his fame? What are his friendships like?

“Vacationland” explores these questions, but never coldly. Hodgman is doing his best to face difficult questions about who he is and who we are. He’s also facing that there are but only so many days he has left with his wife and children. And he’s also realizing that the memories of his mother and his time with her are now all that remains of her, and the same fate will befall him. So while our adorable egghead can target a keen observation at the heart of a matter, he’s also terribly human, modest, and gentle at the same time.

The Case Against Reality by Donald Hoffman

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

In a conventional Western philosophy degree program, the course of study is divided into two primary divisions: ancient (Greek philosophy) and modern (Descartes through present-day). The gap between is dominated by superstition and religion that ends when Descartes re-proposes a fundamentally ancient idea: “Which sense-data are able to be called into doubt (…quae in dubium revocari possunt) and which are not ([quae] perspicuae veritates in suspicionem falsitatis [non] incurrant — Meditationes)?”

According to Donald Hoffman’s book, for practical purposes, none of our senses’ apprehension of the world can be trusted, for they are liars that have been trained by the most patient and skilled algorithmic learning program ever: natural selection.

Guided by game theory payoffs, that is, natural selection, our senses have selected for a non-veridical apprehension of reality that provides humans data enough leading to offspring production for minimal resource inputs (i.e. calories).

Since our apprehension need only be “good enough” for this all-to-animal and carnal purpose, heuristics that lead to error (optical illusion, states of perception incompatible with physics’ experiments) are tolerable as long as the strategy, on the whole, produces evolutionary fitness.

From the Mixed-Up Files Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Last winter I passed by Strand Books and they had this gem of young adult fiction for sale for a measly 48¢. I wondered how this book differed from the movie I remembered as a child. I’m delighted to say that it doesn’t merely hold up, but is actually more rich and more enjoyable as an adult reader. This enjoyability is in part driven by some of the clever narrative structures Ms. Konigsburg used to frame the meta-awareness of the story as it is told. On top of this, it’s also a snapshot of New York before its gritty descent of the late seventies: it’s still a place where a visit with Grandma to the Museum and Schrafft’s with white gloves might have played out over a hazy, warm spring day.

Here Comes Everybody

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

Rating: 3.0 / 5.0

I found this book on a sidewalk in Park Slope about four years ago and I just now got to reading it. I’ve seen Shirky quoted in tech media for many years and loved his talk on how the disruption of mass-urbanization during the 19th century occasioned the proliferation of gin-carts and kiosks that characterized the gin-swilling era we see humorously portrayed in “My Fair Lady.”

In any case, I’m sure this book was much more revolutionary closer to its publication date, but I appreciate that several of the central theses held up. Before getting to the content, I want to raise one frustration about the book’s structure.

Form

Non-fiction / pop-technical book are meant to be read and, in my experience, ought give their jewels away quickly so that the audience benefits and can decide when to go deeper (and how deep to go). This is the heart behind the inspectional reading technique: the belief that writers in this genre tell you what they’ll tell you before they tell it, so that you can track the arc before having made the first formal step.

While many parts of the book didn’t need a deeper read by me (someone within the industry), it’s structure left me guessing as to whether there was some important facet within the next paragraph. There was no real benefit in structuring the chapters like 19th century potboiler serials. The unveiling of the structure at the beginning is perfectly fine. To put it cynically, we’ve already bought the book, now it’s about our payoff, not the author’s.

To the content, though.

Content

The Thesis

Shirky, to his credit, never got too-terribly “Ooh” and “Aah” about insurgent technologies or the people behind them. A few of the technical sites used as examples have not aged well (poor Flicker, Dodgeball, etc.), but this is not a tarnish to Shirky’s observations in the least.

Ultimately, the argument that social technology will make it easier for groups to form and do work that could-not and would-not have been done within organizations like corporations and businesses has been borne out. Previously, to do something big, you needed to make sure that the outcome justified the overhead and synchronization costs. The Catholic Church or the US Army are examples of this. But if the costs of collaboration and group-forming don’t just drop, but fall to zero, people can choose to participate in “big things” for reasons like curiosity or interest. That’s the big idea, and it’s correct. Linux remains strong, the open source ethos has flourished, Wikipedia continues to grow.

Dangerous Possibilities for Collaboration

Shirky even points out that forms of undesirable collaboration were blossoming. While he mentions it at only a superficial depth, he’s diagnosing a lump that wound up metastisizing in the Russian interference with the 2016 election.

[media personality that mobilized a horde of collaborators to name, shame, and undermine someone] benefited from having generated the attention, he was not entirely in control of it – the bargain he crafted with his users had him performing the story they wanted to see.

Boy, that sent shivers up my spine. Consider the manufactured outrage through tools like Facebook.

“Do we also want a world where, whenever someone with this kind of leverage gets riled up, they can unilaterally reset the priorities of the local police department?”

Consider the “SWAT-ing” and “doxxing” operations that hijack the tools of civic order to harass and abuse.

Lastly, Shirky warns that the resiliency that social software offers also means that bad memes (Flat Earth, extermism) can find, organize, and deploy uninformed actors (in addition to bad actors) to create disinformation that can be used to undermine legitimate facts, institutions, and science.

It was a good read. A few highlights are below:

Face It

Rating: 2.0 / 5.0

Rating: 2.0 / 5.0

I’ve loved Debbie Harry and “Blondie” as along as I can remember. I remember seeing Ms. Harry hosting on The Muppet Show when I was a child, admiring the striking Parallel Lines album cover in my parents’ vinyl collection, and loving the rocksteady beat of “Tide is High” from the way-way back of my neighbor’s wood-paneled station wagon at the cusp of the 80’s. Blondie is tied to many of my earliest memories.

In college, I came heavily under the sway of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. From there, I learned more about Television, (early) Talking Heads, the New York Dolls, Berlin-era Bowie, the Stooges, Iggy Pop, the Ramones (under guidance from Stephen King), and…Blondie. That era of NYC creativity is so interesting as Woodstock’s “Summer of Love” faded into, just a few short years later, “NYC Drop Dead” in the Ford administration. In that moment visually “Saturday Night Live” was born and, borne on the shoulders of Long Island or suburban kids come to rest in the Lower East Side, a striking and new music scene emerged.

Ms. Harry was there.

From that punk-era, Harry then underwent a series of interesting artistic transformations: as Warhol’s muse in an Amiga computer art demonstration, as a fatal siren in the disturbing body-horror work of David Cronenberg, and as a canvas for twisted biomechanical ideas under the airbrush of H.R. Giger.

I expected her memoir to reflect and reveal what life at Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s was like. I wanted to see the dirt and the grim that gave her faux-Marilyn angel an edge. But I also wanted to see how she contextualized that lightning-in-a-bottle moment and then how she made sense of what came after, including the Blondie reunion.

But this book failed to meet my expectation. It lacked, and I think this might be an editing error, any “frame” to turn “and this happened and then this happened” into a grander narrative worthy of this icon.

Exhalation

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

I was a stranger to the writing of Ted Chiang until I saw the film Arrival, adapted from his story The Time of Your Life. My friend Linda suggested this collection to me and I’m glad she did. Chiang has a wonderful voice that has a mournful and elegiac quality I love about Ray Bradbury that complements his stories that think through the complicated twists and turns of time-travel, multiverses, and AI.

I’ll list some of my favorite stories in the collection.

The Overstory

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

About two paragraphs into this book, I wrote on social media that I just knew I was going to love this book. And I did. The book starts unconventionally, with single-person focused vignettes about the key dramatis personae. These vignettes stand solidly as wonderful character studies that might have come from Spoon River Anthology. With all of his richly realized pieces on the table, Powers uses the framing device of trees in their multitudinous ways of affecting us, to bring the characters, or the characters’ thoughts together.

It’s a beautiful book and is outstanding for its focus on character, beautiful language, and elegiac tone.

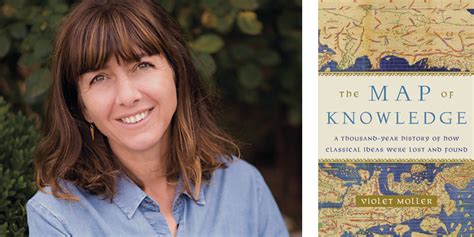

The Map of Knowledge

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Rating: 4.0 / 5.0

Rarely have I read a book whose introductory anecdote so well aligns what the book contains. Moller’s introduction describes the famous mural The School of Athens designed by Raphael in the Vatican. She notes that the popular perception of the Renaissance was that those artists and thinkers like Raphael woke up one fine day, went to a library, re-discovered Classical learning and — violà — The Renaissance. Suddenly science, math, architecture, and governance experience a quantum leap and “civilization,” in a form that the Western modern mind recognizes, returns.

But this is clearly impossible. Knowledge that is not practiced or archived will be lost. It must be curated, maintained, and transmitted.

Asks Moller:

One of his most significant achievements was helping to produce the first English translation of Euclid’s Elements, in 1570. But where had this text been and who had looked after it in the 2,000 years between Euclid writing it in Alexandria [and the 16th century]

They had thrived in the Middle East.

As anyone knows who’s played the empire-building video games like Civilization, first you establish a food supply, then safety as guaranteed by a professional military, and then you get the low-yield/high-payoff leaps forward provided by intellectuals. Because this formula had been lost in religious wars and hamletization in the former territories of the Western Empire, these books found refuge with inky-fingered scholars and magnificence-burnishing enlightened Emirs.

Moller shows that over and over when immigration, tolerance, curiosity, translation and respect thrive under secure conditions, civilization blossoms.

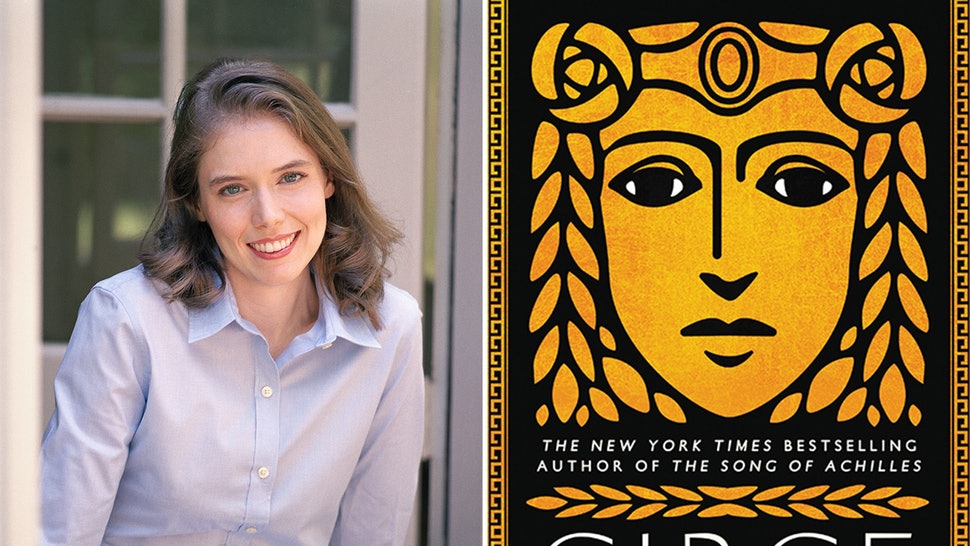

Circe

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

Rating: 4.5 / 5.0

As a fan of Miller’s Song of Achilles, I was excited to read her latest novel, Circe.

Miller’s niche is thoughtful exploration of the society and psychology of the characters in the ancient epics. In particular, she likes to use the perspective of a “minor character” to examine the motivations of the “major characters,” explore the characters’ society, and provide poetic lushness to the stories' settings.

In Achilles she re-lenses the war at Troy through Achilles’ companion, Patroclus; in Circe she re-lenses The Odyssey as well as the Minoan / Argonaut cycle through Circe. Achilles focuses on lovers’ devotions and heroic violence, but Circe’s arenas of contending are intellect, bravery, and politics. Miller’s books are complimentary, but they each have a different perspective on the ancient world.

Circe is an excellent read, a fun story, and a beautifully rich envisioning of the Mediterranean world. Many of my favorite passages hinge on Circe’s description of sorcery and spell-casting. These passages will resonate with makers of things of all media and all capabilities (see notes after the jump). Circe’s language for this work is highly evocative of programming.

Miller also gives Circe some insights about the nature of religion. She notes that it’s a fear and bullying cascade from the top (Zeus) to the bottom (her) based in insecurity which compels the caprice of the gods to ensure lamentations, offerings, and begging continue. In short, to secure the adulation they hold dear, they have to ensure a cascade of misery.