The Failed Promise of Automator and the Failed Promise of AI Workflows

The promise of computing was that it would take drudgery away. And it has: I no longer have to squeeze in a bank visit on a lunch break and I can get disinformation pumped into my home without having to go outside to listen to the town idiot. Up next: flying cars.

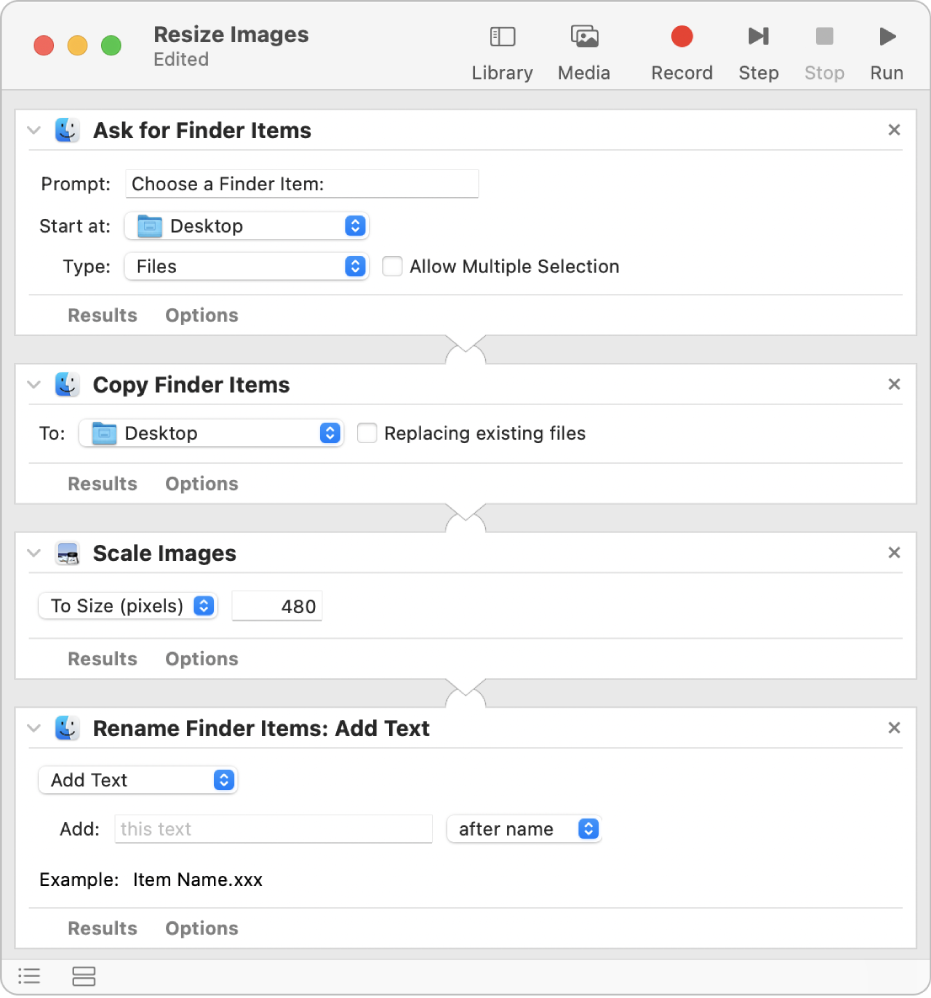

But computing, in doing so, has created digital chores that the more obsessive of us (👋) need help automating away. Ironically then, the automation needs, uh, automation. While tools like AppleScript/Automator suggested a way forward, I’ve not seen their use become commonplace.

Drag and drop your cares away

The drudgery has not been dispelled. Most workflow automation remains “None,” as best that I can tell. Maybe in a push, the wizard class might put in some light coding (👋) to help out. At the outset (2024-current moment), LLMs suggested to me that at last automating workflow development without specialized knowledge could be democratized.

The results were disappointing as ChatGPT-4o bungled the simple task of processing images again and again.1

Let’s use the following lenses:

- Generalized knowledge

- Domain-specific knowledge

- Operating System / Platform ease-of-use or integration

to examine how automation workflow software with Apple’s Automator or LLMs might yet help us bid farewell to our digital chores.

AI Magic vs. The Disappointment: Why AI Feels Both Revolutionary and Broken

I’ve been watching discussions around AI systems since last winter, and I’ve noticed a divide in how people perceive their capabilities. The same technology that leaves some users genuinely amazed leaves others profoundly frustrated. What’s even more interesting, is that the frustrated ones are often the technically sophisticated; the amazed, the technically unsophisticated.

- Token prediction can save lots of work – and that’s magical!

- The inability to build reliable workflows feels like failure to the technically sophisticated

Understanding this divide helps explain why AI discussions often feel like people are talking past each other, and what it means for the future of these technologies.

"To Know" in the AI Age

One of the most charming aspects of English and many other Old-Norse-derived/-cognate languages are kennings. Kennings are words created by bonding multiple words, usually to poetic effect. The Beowulf poet speaks of “the whale road” to mean “the ocean.” Elsewhere, a “sword-storm” describes a battle. The kenning succeeds where its constituent words fall short on the same grounds as Impressionist art:

an artist's work as framework

+ the perceiver's personal history and experience

= living, breathing artistry

The infinitive to know is in need of rescuing.

Over these last ten years, I’ve been party to multiple conversations where misunderstood expectations around to know have hampered effective communication. While “to know” might have been wheezing under the just-in-time epistemology of the internet age, the arrival of AI in workplace, school and home is a type of respiratory failure for this overloaded infinitive.

An example from my own profession: misaligned expectations around “to know” or “knowledge” have proven onerous and lead to frustration on behalf of job role candidate and manager.

But using kennings to examine our usage of this verb might allow us to speak more accurately about our knowledge.